Article: Mental Health Research with Young People

This study aimed to explore experiences of young people, reflectively and retrospectively, who have taken part in mental health research. Findings suggest researchers should nurture the working relationship and provide information about the study clearly, in accessible formats, provide outputs and findings from the study in a timely manner, and get to know the young person, not only their difficulties, during the research process. Adopting a holistic and integrated approach to mental health research across children’s services in collaboration with young people is essential. It should not be assumed family engagement is always possible or positive for the young person.

Introduction

Nearly one in six young people in the UK currently struggle with their mental health (Newlove-Delgado, 2022), with feelings of isolation and anxiety for the future increasing (MacDonald, at al., 2023). Mental health research with young people, families, and care providers is essential to ensure people are offered the right help when they need it, to improve the efficiency of services, and improve outcomes for young people.

It is essential children’s voices inform the services offered to them. It is important for research with young people to take a broad, flexible approach to understanding children’s mental health challenges and needs, working together with stakeholders and children’s services (Fisher, 2022). We know that school-age children want to have choices, clear and easy-to-understand information to help them make decisions, and positive questions included early on when they’re asked to answer surveys about themselves (Demkowicz, et al., 2020). Additionally, qualitative components of research can help amplify the child’s voice and young people may prefer digital, rather than paper and pen, participatory options. Further, due to the inevitability that the researcher’s voice is present in the interpretation of young people’s data, Caldairou-Bessette, Nadeau and Mitchell (2020) advocate for creative forms of data collection that go ‘beyond verbal language’ and that research should be designed to accommodate young people as researchers, as well as participants.

Mental health research can identify disparities in mental healthcare delivery (Ball, et al., 2023), without which, we cannot begin to tackle health inequalities. With greater knowledge of young people’s experiences of engaging in mental health research, we can improve the quality and design of future research, to improve access to and experiences of mental health services.

Methods

Design

This exploratory study examined factors that made research participation meaningful, positive, or challenging, to inform future clinical research. Ethical approval was granted by Lancaster University (FHM-2022-3285-RECR-1). An online survey, hosted via Qualtrics, was adapted from the NIHR Clinical Research Network’s Participant in Research Experience Survey (PRES). Some questions were rephrased in the past tense due to the reflective nature of this study. Participants were also asked to share advice for future mental health research involving young people and families.

Participants

Eligible participants were adults (18+) with experience of participating in mental health research before the age of 18, or parents/carers of those who had. Recruitment was via social media and the Voice Collective network. Seventy-one participants (33 male, 38 female) completed the PRES, with 22 providing qualitative responses. Seven duplicate or inauthentic entries were excluded prior to analysis. Due to varying response lengths, findings are presented as a summary rather than a detailed qualitative analysis.

Participants had previously engaged in research while receiving treatment for anxiety (42%), unusual sensory experiences (24%), depression (20%), or psychosis (7%). No participants selected the ‘other’ category. All identified with the same gender as registered at birth, born between 1981 and 2002, with 44% participating as participants in research as young people and 56% as parents/carers.

Results

Satisfaction ratings from participants in this study were noticeably lower than the national averages for adults and young people taking part in NIHR portfolio studies (2021/22 PRES), indicating the quality of engagement experiences across a wider range of research activities is variable.

Table 1: Responses to the adapted PRES

|

PRES Item |

% of participants with favourable response*

|

||

|

|

Current Study |

CRN 2021/22 adult participant survey[1] |

CRN 2021/22 CYP participant survey |

| The information that I received before taking part prepared me for my experience on the study |

80 |

95 |

90 |

| I feel I was kept updated about the research |

59 |

82 |

86 |

| I knew how I would receive the results of the research |

39 |

79 |

78 |

| I knew how to contact someone from the research team if I had any questions or concerns |

60 |

90 |

87 |

| I felt research staff valued my taking part in the research study |

62 |

92 |

95 |

| Research staff always treated me with courtesy and respect |

65 |

97 |

92 |

| I would consider taking part in research again |

65 |

93 |

92 |

*Answering strongly agree/agree to the statement provided

Thematic summaries of qualitative data are provided in relation to the three questions posed.

What was positive about your research experience?

Participants discussed how being involved in research made them feel. For example, “I felt good about contributing toward better patient care in the future. The psychologist really appreciated me taking part and was kind to me”; “It makes me feel better”. Engaging with mental health research facilitated a greater connection between the young person and the people providing their care, and perhaps encouraged everyone to “pay more attention to the mental health of the people around them”. “Reducing negativity” and enhancing a “sense of direction” at a time when people can feel disheartened or lost were also positive features identified. Finally, learning from experience, developing collaborative relationships, “put a face to their names and have informal interactions”, having ample time for activities, remuneration, and feeling in control of choices were all aspects of positive research experiences.

What would have made your research experience better?

Improved working relationships, communication, and access to research findings were identified as areas for improvement. Considering the “opinions of all parties” involved, creating a “soothing” space around participation, and making the experience “convenient” for participants were also noted. One participant reflected they felt “alone” and “judged” during the research experience as the researchers did not engage with them directly at times and the research seemed to feel like more of a “test” than a space to “heal”.

What would be your advice for future mental health research with young people and families?

Participants stated the need for clear explanations and accessible communication, such as though creative mediums, about what the research is about. Due to power imbalances, which can be amplified in some environments (e.g., inpatient settings), it was seen as highly important for the researcher(s) to develop a collaborative relationship with the young person.

There were also recommendations to “increase psychology”, to hold in mind people’s physical and mental health regardless of the focus of the specific study being undertaken, and to “pay attention to their emotions at ordinary times”, which seemed to imply a holistic knowledge of the young person, rather than only focussing on their ‘problems’ or crisis points.

The involvement of families, schools and communities was also mentioned as potentially supportive to research with young people. However, one participant highlighted that it is important researchers do not “assume family are safe or helpful to a young person”. Relating to the young person on their own terms, in private, and “as a human being, not as a researcher/clinician” was also highlighted as important to support the working relationship in a “meaningful” process for all involved.

Discussion

The quality of the engagement experience for young people in research could be improved. Specifically, further efforts should be made to tell young people how they will receive information about the findings of the research study they take part in. Data from the current study highlighted providing information clearly and accessibly is particularly important if the young person is still in treatment at the time of research participation. Furthermore, young people may not always be able to see what is being done for research purposes and what is treatment, and therefore what this means for the options, timings, and consent around their engagement if this information is not explicit.

A particularly negative encounter in which a participant felt ‘judged’ was within inpatient care. Therefore, researchers should carefully consider the environment the young person is in within the research context, especially in relation to how this environment may influence the young person’s experience of choice, freedom, and control over their decisions. It may be helpful for researchers to draw upon principles of trauma-informed care for research in inpatient settings (Saunders, et al., 2023) to mitigate harm and promote compassionate safety.

Conclusions and Implications

Whilst this brief study did not generate data suitable for an in-depth qualitative analysis, it nonetheless foregrounds the often-overlooked voices of young people in research. In doing so, this reflective study offers an opportunity to learn from participants’ lived experiences, highlighting the importance of making space for perspectives that are too frequently marginalised. One limitation of the study is that it did not control for the type of research participants had previously taken part in, such as clinical trials or service evaluations. However, this openness can also be viewed as a strength, as it enabled the inclusion of a broad range of experiences, including those outside the context of National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) portfolio studies. As such, the report provides insight into accounts that might otherwise remain unheard.

Findings from this study suggest that research engagement experiences beyond NIHR portfolio studies may be less satisfactory, with some indications as to why less well-resourced projects might struggle to provide an optimal experience for young participants. Notably, the open and inclusive nature of this study also highlighted experiences from a subgroup of young people who reported unusual sensory experiences, such as hearing voices or seeing visions. This is an important and under-researched area within child and adolescent mental health, despite evidence suggesting that up to 50% of children receiving care through Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) report such experiences (Jolley et al., 2018). The inclusion of these voices underscores the value of exploratory research that captures diverse and often marginalised experiences.

These insights align with wider concerns about health inequalities in both clinical care and research participation, as we know healthcare inequalities are often reflected in research (Fairchild, 2019). The findings support calls for future research to actively seek the views and feedback of young people from under-served and underrepresented communities. Such work could help identify areas where research engagement practices might be improved to foster more inclusive, meaningful participation. Ceballos, Taylor, and Turner (2023) argue for the need to consciously dismantle structural racism in the design and delivery of research by adopting participatory methodologies such as Participatory Action Research and creative, co-produced approaches. By embedding these methods, future studies have the potential not only to reflect the needs and priorities of a broader range of young people but also to involve young people in shaping the research questions, processes, and outcomes that directly affect their lives.

In summary, it is crucial to adopt inclusive and flexible approaches when involving young people in mental health research, recognising that their experiences of research participation remain underexplored. The perspectives of those who have engaged in research, alongside those of their parents and carers, offer valuable guidance for the design and delivery of future studies. In clinical practice, consideration should be given to involving young people as experts by experience, co-researchers, or participants, depending on their individual needs, wellbeing, and stage of treatment. Ensuring that young people are offered safe, supportive spaces in which to engage, with opportunities to reflect on and process their involvement, should be a priority. Ultimately, services for children and young people should foster emotionally safe, inclusive, and collaborative environments where young people feel heard, informed, and valued, and where they are given meaningful opportunities to shape the services and research that affect them.

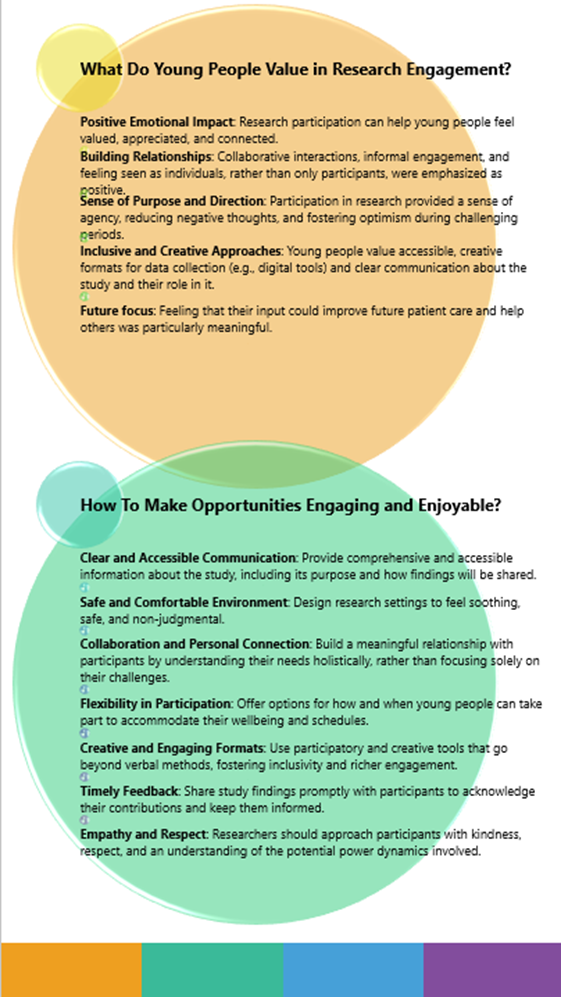

A summary list of what young people value in research engagement and how to make opportunities engaging and enjoyable.

A list of recommendations for Involving Children and Young People in Research is also available here.

[1] From: NIHR Clinical Research Network (CRN) (2022). Participant in Research Experience Survey (PRES) 2021/22. https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/participant-in-research-experience-survey-pres-202122/31768

Youth & Policy is run voluntarily on a non-profit basis. If you would like to support our work, you can donate any amount using the button below.

Last Updated: 18 July 2025

Footnotes:

Funding: This study was funded by Emerging Minds, a research network funded by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) between 2018 and 2022, based at Oxford University.

Additional information: Original questions in the PRES as used by the CRN

Q1: The information that I received before taking part prepared me for my experience on the study.

Q2: I feel I have been kept updated about the research.

Q3: I know how I will receive the results of the research.

Q4: I know how to contact someone from the research team if I have any questions or concerns.

Q5: The researchers have valued my taking part in the research.

Q6: Research staff have always treated me with courtesy and respect.

Q7: I would consider taking part in research again.

References:

Ball, W. P., Black, C., Gordon, S., Ostrovska, B., Paranjothy, S., Rasalam, A., & Butler, J. E. (2023). Inequalities in children’s mental health care: analysis of routinely collected data on prescribing and referrals to secondary care. BMC psychiatry, 23(1), 1-18.

Caldairou-Bessette, P., Nadeau, L., & Mitchell, C. (2020). Overcoming “you can ask my mom”: Clinical arts-based perspectives to include children under 12 in mental health research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1609406920958959.

Demkowicz, O., Ashworth, E., Mansfield, R., Stapley, E., Miles, H., Hayes, D., … & Deighton, J. (2020). Children and young people’s experiences of completing mental health and wellbeing measures for research: Learning from two school-based pilot projects. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14, 1-18.

Fairchild, G. (2019). Mind the gap: evidence that child mental health inequalities are increasing in the UK. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28, 1415-1416.

Fisher, H. L. (2022). The near ubiquity of comorbidity–what are the implications for children’s mental health research and practice?. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(5), 505-506.

Jolley, S., Kuipers, E., Stewart, C., Browning, S., Bracegirdle, K., Basit, N., … & Laurens, K. R. (2018). The Coping with Unusual Experiences for Children Study (CUES): A pilot randomized controlled evaluation of the acceptability and potential clinical utility of a cognitive behavioural intervention package for young people aged 8–14 years with unusual experiences and emotional symptoms. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(3), 328-350.

MacDonald, R., King, H., Murphy, E., & Gill, W. (2023). The Covid-19 pandemic and youth in recent, historical perspective: More pressure, more precarity. Journal of Youth Studies, Advanced Access. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2022.21638

Newlove-Delgado, T., Marcheselli, F., Williams, T., Mandalia, D., Davis, J., McManus, S., Savic, M., Treloar, W. & Ford, T. (2022). Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2022. NHS Digital, Leeds.

NIHR Clinical Research Network (2022). Participant in Research Experience Survey (PRES) 2021/22. https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/participant-in-research-experience-survey-pres-202122/31768

Saunders, K. R., McGuinness, E., Barnett, P., Foye, U., Sears, J., Carlisle, S., & Trevillion, K. (2023). A scoping review of trauma informed approaches in acute, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care. BMC Psychiatry, 23, 567. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05016-z

Biography: