Article: Equitable Evaluation: Co-developing evaluation with young people in a community makerspace

Jennifer DeWitt and colleagues explore how evaluation with young people can be more equitable through a community makerspace project. Working with Knowle West Media Centre, a team of Researchers and Practitioners extended the participatory aspects of their evaluation practice to support the agency of young people.

Introduction

Youth programmes, whether in youth work settings, community programmes or other out-of-school locations, are increasingly faced with demands for accountability, inextricably linked with a need for evaluation evidence. However, as argued by de St Croix and Doherty (2024) and others (e.g. Zeller-Berkman et al., 2015), traditional evaluation measures often do not sit comfortably with aims of youth work which centre on amplifying youth voice, supporting social and emotional development/ safety, fostering a sense of belonging, and encouraging autonomy and agency (Begley, 2021; Brightpurpose, 2019; de St Croix & Doherty, 2023; Osai et al., 2024). These aims often do not lend themselves easily to standardised measures such as attainment scores or other quantitative measures designed for formal education or school environments.

In contrast, equitable evaluation is evaluation conducted in an equitable manner (e.g. with care, responsive, centring relationships) and directed towards equitable/social justice ends. Equitable evaluation practices elevate, respect and value the experiences, perspectives and contexts of participants and offer a framework for conducting evaluation that is more aligned with youth work aims (Stern et al., 2019). In order to contribute to more inclusive and equitable practice, evaluation should ‘privilege the voices and lived experiences of non-dominant communities, engage communities in identifying desired outcomes, and ensure multicultural validity of instruments, measures, and inferences’ (Garibay & Teasdale, 2019, p. 87). As such, these principles of equitable evaluation are particularly well-suited for youth work programmes.

Co-production of evaluation

Co-production offers one approach to implementing equitable evaluation principles in youth work settings. Co-production is a process whereby responsibility, authority and agency are shared among contributors (Robinson, 2021), so that involvement benefits all participants to an equal degree (Co-production Collective, n.d.). In the case of evaluation in youth spaces, this would mean involving young people in the processes of evaluation, rather than solely as respondents. Although participatory evaluation approaches, which likewise involve youth in evaluation processes, are increasingly utilised in youth work settings (Cooper, 2017; Zeller-Berkman et al., 2015), these sometimes come into conflict with other structural issues, such as expectations from funders and policymakers. Thus, one critical question framing co-production of evaluation in youth work concerns the relationship between evaluation and programme aims, including who holds power in shaping these aims. Working with a youth-focussed makerspace programme that faced similar tensions, this paper explores the journey of the makerspace (re)thinking how equitable evaluation can support the agency of their young people and the evolving practice of their organisation. This work adds to the field’s understanding of how co-produced evaluation can be supported in youth work settings and resonates with calls to involve youth more in programme evaluation; de St Croix & Doherty, 2024).

Working with a community makerspace

The work described in this article was undertaken as part of Making Spaces, a project that aimed to develop and share equitable practice in makerspaces, collaborating with six partner settings. Makerspaces are shared spaces, often based in community organisations, schools or museums which support innovation and tinkering projects using digital and non-digital technology and other equipment. One of the project’s participating spaces, The Factory, located at Knowle West Media Centre (KWMC), has a longstanding commitment to equitable practice and is deeply embedded in and responsive to its community. While equity and participatory practice were already core to their work, staff involved in this project (many of whom had a youthwork background), wanted to extend the participatory aspects of their evaluation practice so as to further support the agency of young people in their makerspace.

In this article we draw on data collected in partnership with this community makerspace to address the research question of how evaluation – and co-production of evaluation in particular – can be used to support youth agency and voice? A rich dataset was collected around KWMC’s activities as part of the Making Spaces project, a subset of which concerned evaluation activity and was analysed in addressing our research question. We utilised observations of three sessions involving co-production of evaluation and notes from five reflection meetings with makerspace practitioners, audio and video recordings of young people working on evaluation, images of evaluation tools created, and three interviews with practitioners and three with young people working on evaluation. We took a broadly thematic approach to analysis, weaving together multiple data sources to create a narrative case study of the co-production of evaluation in The Factory. We triangulated data sources, with particular emphasis on interview data and conversations with young people. These helped us gain insight into instances when young people seemed to be exercising agency and pointed to opportunities to further elevate youth voice.

Co-producing evaluation at a community makerspace

KWMC has always aimed to use equitable approaches to engagement, often drawing on youth work principles in their activity with young people. For example, they run a regular youth council to incorporate youth perspectives into their planning and adopt a coaching approach to facilitation to ensure young people’s voices are fore-fronted. They used the opportunity of the Making Spaces project to explore how they could expand their evaluation practice to involve youth in equitable and participatory ways.

The three trialling sessions

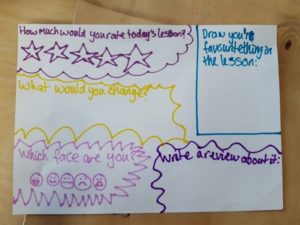

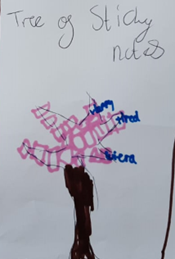

In early 2023, The Factory introduced activities in three programme sessions that aimed to trial ideas around co-producing evaluation with participants aged 11-16 years. In the first session, staff introduced the evaluation focus and explained the aim to co-produce new practices. The first activity involved supporting young people to come up with new ideas for evaluating their experiences at the makerspace. The young people designed a wide range of new tools, including short surveys (which used smiley faces, icons, numbers and words, and drawing) as well as other creative tools such a ‘feedback tree’ where people could write ideas/reflections on paper ‘leaves’ and stick them on to a wooden-branch structure (Images 1 and 2).

Image 1: Survey designed by young people

Image 2: ‘Feedback tree’ design

In the second session (several weeks later), practitioners produced the young people’s different ideas at several evaluation ‘stations’ at the end of the session and organised an activity where the young people could first try out each evaluation tool, and then in a second step ‘vote’ (using post it notes) on their favourite tools (Images 3 and 4). Practitioners then led an open discussion with the young people on their likes and dislikes for the different tools. For instance, many enjoyed creative evaluation approaches, such as ‘head, heart, feet’ (something you have learnt, how you felt, what you want to do next) or summing up the session in a single word, as well as drawing. Others preferred online tools, so as not to waste paper.

Image 3: Feedback tree

Image 4: Post-it note voting on favourite evaluation tool

The third session was an end-of-term showcase, where the selected ‘favourite’ evaluation tools designed by the young people were tried out. These tools included the feedback tree, an online survey, and other approaches previously used by the makerspace that the young people reported enjoying. One young person also took his own initiative to create and monitor an evaluation station (a table with surveys he had created) to gather feedback on his work. To develop the questions for the online survey, a practitioner and funder engaged a small group of young people before the showcase opened. The discussion reflected youth agency, as young people led the conversation on question formats and content. For instance, as part of their equitable practice, staff encouraged young people to introduce themselves and their preferred pronouns at the beginning of each session, but one young person recognised this as potentially problematic: “I’m going to say, ‘do you ever feel uncomfortable during the start when you say your name and pronouns?’”

Other young people addressed the format of evaluation questions (drawing) which is often advocated as ‘good practice’ because it does not rely on writing skills: “Some of them ask you to draw and I’m not very good at drawing. So I find it easier just to write it. Like I think it is good to have the option to draw it but…”

Practitioner and young people’s reflections

Throughout the project and after, reflections by youth and practitioners supported the makerspace’s journey towards more equitable evaluation practice, that could elevate young people’s agency and voice. At a basic level, the sessions enabled the makerspace to understand young people’s evaluation preferences. They had the opportunity to express which methods and tools they enjoyed, as well as what they did not like. As these young people discussing feedback form questions demonstrate:

Young person 1: I like the one word one, that’s fun.

Young person 2: It’s good to have the option of saying more there, if you want to. Yeah, you don’t just have like one tiny little space to write a word. You might say more, but also when you’re tired afterwards and you off to do something else. You do want to be able to write down quickly.

Young person 1: I like to circle and use one words – these are easy and quick…. and then like shows a lot in a tiny thing.

The conversations between young people (as above) also highlighted a challenge around the time it takes to do evaluation, and how young people want it to be ‘easy’ and ‘quick’ to do. This led practitioners to reflect on the frequency of the evaluation that they conduct and whether it might be more valuable and less onerous to do it every two or three sessions, rather than every week, and to allow time for collaborative reflection. Practitioners also considered ways to reduce evaluation burdens, such as by offering youth an opportunity to select from resources their peers have already created, rather than creating new tools each session. Practitioners were keen to implement and use the feedback they had gathered from young people:

Of course we are going to carry on the learnings that we got last year, about the evaluation. Keep evaluation quick and subtle and fun and lots of options, yes we have definitely learnt from that and we are going to embed it long-term.

The trialling sessions were also seen to build young people’s ownership and agency of evaluation practices in the makerspace. By equipping young people with a better understanding of evaluation (e.g. understanding differences between rating questions and open questions), they were able to contribute to meaningful discussions around which tools to apply and take an active role in decision-making. For example, young people were involved in deciding what tools to use in the showcase, positioning them as experts. Practitioners noticed that this scaffolded youth facilitation in the showcase, as young people helped visitors to engage with the different tools and took initiatives to gather their own feedback on their work. The staff were happy with this outcome as it reflected a greater sense of ownership in the programme, which they continually hoped to instil:

For meaningful co-production to take place, all stakeholders must be involved from the start. By embedding creative evaluation and recognising young people as experts in their own experience, we gain clearer insight into what works best for them, ensuring that ownership of the process is shared.

The practitioners also reflected that they might have overly focused on supporting young people in the design and creation of methods/ tools and felt that they could have engaged the young people more in thinking about the purpose of the evaluation – why they are doing it and who it was for (e.g. respond to funders, inform further activities, shape future programmes). As a practitioner noted: ‘I think there were quite a lot of why questions that made us as an organisation ask, why are we doing this? What is the best way of using our evaluation after?’ This led to questions around how young people can benefit from evaluation, and how they can take practice further than co-designing different tools to use. Moving forward, staff discussed plans to expand the ways in which evaluation is used, with considerations of how they could involve youth throughout various stages, supporting their agency and using evaluation as a tool to amplify youth voice.

While the process of co-production of evaluation had an impact on how the practitioners and organisation approached evaluation, questions remain about how participation impacted the young people themselves. In later interviews, for example, young people struggled to remember the evaluation activities. Additionally, practitioners worried about how involving young people in evaluation activities takes time away from main activities in the makerspace. Nevertheless, the young people asserted that being involved in the development of the evaluation tools was important, and felt that youth should be involved in co-producing evaluation. In the words of one youth participant: ‘[young people] could, like, make the questions that people want to be asked, not just the kind of rinse and repeat questions that are always asked … and ask questions that are more meaningful for the project’. It was also clear that participating young people had benefited by gaining new skills, such as writing survey questions and identifying best approaches, which was evident in how quickly and efficiently they were able to develop the online survey tool for the showcase.

What came next at The Factory

Following their initial attempts at co-producing evaluation with young people and after subsequent reflection, the KWMC team continued to work on embedding youth-led evaluation into their everyday practice and devised several new ideas. For example, to support youth leadership and agency, they introduced a ‘mini-manager’ role, where young people lead certain aspects of a makerspace session, including an evaluation activity. Every week, the Mini Managers create an evaluation question and decide how to collect the data. The staff turn responses into an infographic, which fuels further discussion and programme decisions, and feeds into the KWMC evaluation matrix. To support young people’s emotional and learning development through evaluation, a ‘time capsule’ activity was introduced, where young people write a letter to themselves at the beginning of term about what they would like to get out of the programme, then another letter at the end, reflecting on what they have learned. They also set up a skills board where young people post skills they possess – which may or may not be related to the programme (e.g. making bacon sandwiches), positioning young people as experts to whom their peers can turn for help when needed. As young people added skills during the term, the board became a visible marker/ tracker of progress and a way to build confidence. New skills survey questions were also added to existing evaluation tools, interwoven with the board, to create equitable, responsive, robust and useful evaluation both for participants and for reporting requirements. Young people also help interpret evaluation data, reflecting with staff on the data and infographics produced, identifying potential changes and checking that their feedback is making a difference.

Over the course of the project and beyond, the staff came to value evaluation as a way of centring youth voices. Equitable, co-produced evaluation is now central to the organisation, informing individual programmes and wider organisational strategy, including current programme redevelopment efforts:

We want to make sure that the programme that we’re redeveloping is totally youth-led and is meeting the young people – their needs. … For us, it [co-production of evaluation] is this ongoing kind of relationship and equity between staff and young people; to make sure we’re in constant communication and learning from them, letting them hold us accountable. Making sure we’re doing what we need for the programme, but also for their needs.

Conclusion

Co-produced evaluation was a logical ‘next step’ in The Factory’s ongoing efforts to centre youth voice, enabling young people’s voices to inform organisational activity in a systematic way, such as through the organisational evaluation matrix and strategic development. In this case, alignment between evaluation practices and organisational ethos not only strengthened evaluation and the learning that emerged from it but also supported organisational development.

Through co-production, commitment to equity and good youth work practice, The Factory involved young people in evaluation in ways that supported their agency and ownership as well as providing insights into ‘what works’ for participating young people within the space. Coproducing evaluation with young people meant that tools were meaningful and relevant to young people. However, not all outcomes captured by youth-developed tools were necessarily equitable, and questions remain about how youth understand some of the purposes of evaluation, as well as about whether young people benefit as much from the process as the organisation does. Nevertheless, we argue that The Factory’s evaluation journey illustrates how co-producing evaluation – where youth work closely with staff to design and collect data on questions and issues that they care deeply about – can represent a valuable tool in youth work efforts to continually advance equitable practice.

Youth & Policy is run voluntarily on a non-profit basis. If you would like to support our work, you can donate any amount using the button below.

Last Updated: 6 February 2026

Acknowledgements:

The Making Spaces project was generously funded by a grant from Lloyds Register Foundation, Grant Number GA\100460.

References:

Begley, S. (2021). An assessment of the value of science, technology, engineering arts and mathematics delivery in the youth work setting in Ireland. Accessed via https://www.youth.ie/articles/steam-in-your-youth-work-5-key-takeaways/ (n.d.)

Brightpurpose. (2019). The role of informal science in youth work: Findings from Curiosity round one. London: Wellcome. Accessed via: https://wellcome.org/reports/role-informal-science-youth-work-findings-curiosity-round-one

Cooper, S. (2017). Participatory evaluation in youth and community work. London: Routledge.

de St Croix, T., & Doherty, L. (2023). ‘It’s a great place to find where you belong’: Creating, curating and valuing place and space in open youth work. Children’s Geographies, 21(6), 1029-1043.

de St Croix, T., & Doherty, L. (2024). ‘Capturing the magic’: grassroots perspectives on evaluating open youth work. Journal of Youth Studies. 27:4, 486-502.

Garibay, C., & Teasdale, R. M. (2019). Equity and evaluation in informal STEM education. In C. Fu, A. Kannan, & R. J. Shavelson (Eds.), Evaluation in Informal Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Education. New Directions for Evaluation, 161, 87–106.

Osai, E.R., Campbell, S.L., & Greer, J.W. (2024). How social justice shapes youth development: Centering youth voices across shifts in out-of-school time. Children & Schools, 46(1), 17-25.

Robinson, M. (2021). How to…. Co-create an evaluation. Centre for Cultural Value. Accessed via: https://www.culturehive.co.uk/CVIresources/how-to-co-create-an-evaluation/

Stern, A., Guckenburg, S., Sutherland, H., & Petrosino, A. (2019). Reflections on applying principles of equitable evaluation. The Annie E. Casey Foundation. Accessed via: https://www.wested.org/resource/reflections-on-applying-principles-of-equitable-evaluation/

Zeller-Berkman, S., Muñoz-Proto, C., Torre, M.E. (2015). A Youth development approach to evaluation. Afterschool Matters, Fall 2015, 24-31.

Biography:

Jen DeWitt is an independent researcher and evaluator and was a senior researcher on the Making Spaces project. Louise Archer is the Karl Mannheim Professor of Sociology of Education at UCL IOE and PI on Making Spaces. Esme Freedman, Meghna Nag Chowdhuri and Qian Liu are also UCL-based researchers. Clara Collett, Megan Ballin and Ellen Havard were practitioner partners at KWMC The Factory and collaborators on the Making Spaces project.