Article: Beyond Brexit: The Impact of Leaving the EU on the Youth Work Sector

The UK having voted to leave the EU, Annette Coburn and Sinéad Gormally consider potential problems and possibilities for youth work within post-Brexit Britain, with a focus on Scotland in particular. They outline how youth work has reached a ‘tipping point’ in its evolution, where austerity measures have consistently undermined it. They examine the potential impact of the further loss of EU funding. Recognising that it is entirely uncharted territory, they assert that despite the inherent concerns, Brexit could also be a catalyst for re-imagining youth work as a creative and resistant practice within social and informal education.

Background

On the 23rd June 2016, 52% of the UK electorate who turned out to vote in the EU Referendum, stated their wish to leave the European Union. Whether this was a protest vote, an anti-establishment vote or a vote of no confidence in the EU, the impact will be long lasting. Arguably, young people may feel this impact more acutely than many, particularly given that (according to Moore, 2016) the under-25 age range were more than twice as likely to vote ‘Remain’ (71%) than to ‘Leave’ (29%). In this referendum, as the age of the voter increased, so too did the likelihood of voting to leave the EU, with over 65s twice as likely to vote ‘Leave’ than ‘Remain’. Drawing on Bruter and Harrison (2016), Helm (2016) reports that ‘the referendum stimulated feelings, particularly among young people, of “sadness but also ones of anger and frustration at people who voted to leave, and often at older generations”’.

This article is based on a briefing paper we produced in February 2017, in response to a request from YouthLink Scotland to offer an overview on which to brief elected officials and other interested parties, on the potential impact of Brexit, and the difference this decision might make to young people, youth workers and youth projects. The extended context for this specific interest group is broad ranging. It incorporates economic, legal, political and social aspects such as, employment prospects, human and social rights, ideological perspectives on community and youth work development, and the social mobility and integration of people across a post-Brexit Europe. In a general sense, while recognising the importance of such extended contexts, we quickly recognised that our brief required a micro-focus on the specifics of the impact on youth work itself. So, while our analysis and subsequent conversations have been set within this wider context, we remain focussed on concerns for the future for youth work and those, young people and youth workers, engaged in its practice.

The article is informed by desk-based analysis of Scottish specific data on Erasmus +, international youth exchanges and social return on investment, combined with wider UK sources in terms of relevant literature. Although much of the data were drawn from Scottish sources, it is our understanding that similar information is available in other parts of the UK and so, despite its geographic focus, we believe that the concerns raised will resonate with other parts of the UK. Our conclusion notes that there is a need for more research and further dialogue across all parts of the UK.

Where are we now?

The impact of leaving the EU on the youth work sector is as yet unknown. What is known, however, is that youth work across the UK has experienced a steady range of cuts in public funding since the current economic crisis began in 2008 (Unison, 2016a). It is also known that young people have been disproportionately affected by this economic crisis where unemployment is higher than for any other age group (Unison, 2016a); they are in more precarious jobs, have lower wages, and are ‘torn between their aspirations…and their need for income’ (Standing, 2011: 74). Further, the European Commission (2014: 12) identified that ‘there is a growing use and reliance in EU level support and financing for the youth work sector as other sources of funding at national level are reduced’.

Our concerns about the impact of ‘Brexit’ on youth work in Scotland specifically (but not exclusively) are grounded in contribution analysis as a logical method for informing understanding of what might reasonably be possible in the future (see Mayne, 2012). Contribution analysis is not an infallible method as illogical or unexpected events can redefine possibilities and make it difficult to develop a logical pathway for change. However, in these times of uncertainty, with increased demand on youth work to engage young people in times of deep-rooted economic crisis, we know that ‘there is pressure to do more with either the same or less funding than before’ (European Commission, 2014: 13). Thus, we use logic in our analysis of what is known in order to consider the problem of ‘Brexit’ for youth work. This analytical frame, as well as wider conversations across the UK, lead us to assert that the potential impacts we identify also resonate beyond Scotland, both within the UK and across the EU.

Considering the impact of leaving the EU on the youth work sector

Our initial assertion at this time of change and uncertainty is to note that youth work has reached a ‘tipping point’. Gladwell (2000: 12) defined this term as ‘the moment of critical mass, the threshold, the boiling point’. With Unison (2016a: 4) estimating that ‘…between April 2010 and April 2016, £387m was cut from youth service spending across the UK’, sustaining quality youth work provision is becoming more difficult. Specifically in Scotland, a survey carried out by Unison (2016b: 4) on the impact of austerity for youth workers found that ‘79% of those who responded stated that there had been cuts or severe cuts to their team budgets this year, 82% said the same about “last year” and 83% said they had experienced cuts or severe cuts over the last five years’. Despite the Christie Commission calling for preventative spending, cuts to local government spending in Scotland have increased (Unison, 2016b).

The subsequent stress and strain of service cuts that workers face impacts on their morale (Unison, 2016b), and potentially there is a risk of ‘burnout’ through self-sacrifice (Hughes et al, 2014: 5), as workers are required to do more, beyond their contracted hours, in order to sustain practice. This loss of resource for youth work projects takes this tipping point to a more critical level than ever before, thus any loss of investment due to leaving the EU will present extreme challenges to a sector that is already struggling to sustain the minimum level of services. It could also impact on the CPD opportunities that are currently available to practitioners through international partnership working and youth exchanges which align with the National Youth Work Strategy 2014-19 to build workforce capacity (YouthLink, 2014). A lack of CPD opportunities is combined with evidence that over 70% of youth workers saw an increase in their workload in the last few years (Unison, 2016b). Taken together, this means that an already stretched workforce will have reduced capacity for innovative and creative youth work responses to as yet unknown social and political scenarios and emerging new contexts.

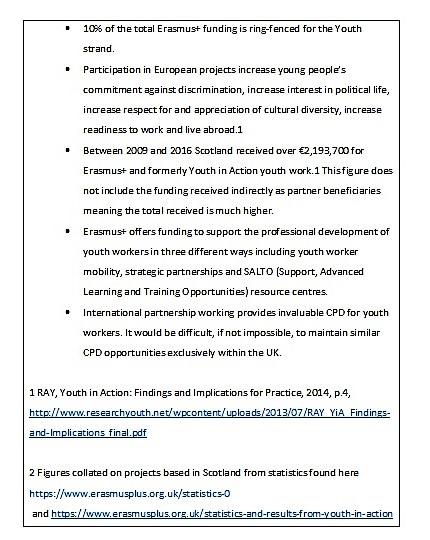

The Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 (Scottish Government, 2015) and the statutory regulations on the Requirements for Community Learning and Development (Scottish Government, 2013) which promise to reduce inequalities and ensure local services are managed by local communities, are compromised by the reduced infrastructure for youth work. Against this backdrop, there are obvious impacts of Brexit on the already increasing financial gap in the level of investment in youth work projects. Currently, youth projects and services receive significant levels of funding via Erasmus+ and workforce investment, as demonstrated in figure 1 (extracted from Beever and Green, 2017).

Figure 1: Extract from Beever and Green (2017)

The level of investment from Erasmus+ and similar previous EU funding programmes, has underpinned a long-standing engagement with EU partners in promoting understanding and facilitating mobility across the EU through international youth exchange programmes (European Commission, 2001). These schemes have also facilitated the mobility of youth work students who have come to, and travelled from, Scotland and across the EU in order to undertake youth work practice placements. Incoming and outgoing student exchanges have brought international perspectives to the youth work workforce and more directly to the heart of our most deprived communities. This has added a social benefit in transmitting important values of social justice, equality, citizenship and sustainable development (European Commission, 2014; European Union, 2009).

According to Mayne (2012) logical claims to contribution are strongest when they provide a mix of contextual information, the perspectives of beneficiaries, and theoretical and research information. Thus, in addition to information provided on EU funded projects (figure 1) and student exchanges, we also draw on longitudinal research on international youth exchange work. This research shows that youth exchanges created chances for young Scots to meet with young people who were different to them, and whose beliefs and values were different to their own. Articulated as a border pedagogy (Giroux, 2005), this research identifies that crossing social and cultural boundaries helped young people to learn about difference, and promoted mutual understanding, trust and the building of social and cultural capital (Coburn, 2011).

The research also shows that international youth exchanges engage young people in developing a range of practical skills in negotiation, planning and leadership (Coburn and Wallace, 2011), all of which impact on participants’ lives beyond their time engaged in youth work. The young people involved in the research describe their experiences of an exchange as life-changing. This kind of work is firmly established across Scotland and embraces the EU values and principles of equality and social justice, to bring benefit to youth work practice across Scotland. Applying the logic model, if EU funding for youth work projects and youth exchanges is no longer available to the Scottish sector, it can be argued that the contribution of youth work to enhancing young people’s capacity for social and cultural connectedness, for understanding and accepting difference, and for using such experiences in formation of their own identity, will be clearly impacted.

Of course, investment of EU funding for youth work is only part of the story in considering its value. In a study commissioned by YouthLink Scotland, Hall Aitken (2016) estimated that the social return on investment in youth work is that it contributes £656 million to the Scottish economy and shows a return of £7 for every £1 of public money invested. Their findings show that:

- Youth work contributes at least £656 million to the Scottish economy;

- Youth work has made a major difference to the lives of over 450,000 people in Scotland today (over 13% of the Scottish population);

- The confidence and motivation that involvement in youth work facilitates young people to develop is rated by 85% of employers as ‘very important’, compared with 27% of employers rating qualifications as such;

- The social return on investment of youth work is at least 3:1.

Thus, a reduction in available spend, which might be reasonably anticipated in a post-Brexit scenario, would impact on the current social return that youth work contributes to the Scottish economy and to our young people.

Where might we be going?

While we recognise that the impacts identified here are not fully inclusive of the range of investments in youth work projects from the EU, across the UK they do give an indication of the iterative effect of how such a loss of funding is potentially damaging to an already damaged sector. Yet, we retain some optimism despite the uncertainties of the current situation.

Bauman (2000; 2012) uses the term ‘liquid modernity’ to denote this period of history as a time where contrasting ideas, positions and values exist alongside each other and can be moved back and forth between fluidly. This leads to feelings of uncertainty about what is actually real or true so people seek core ideas to help sustain an otherwise precarious existence. Bauman offers hope in the idea of networked communities, whereby human interactions and identities are sustained because individual people find shared beliefs and values about what is important. In this sense, we have argued that the concept of community, for example, ‘has utility for community practices that are aligned to social movements for change, in connecting people around a particular cause or interest’ (Coburn and Gormally, 2017: 84).

In asserting youth work’s position as a discrete ‘community of practice’ within education (Wenger, 1998), we believe that connected conversations can help in counteracting the precariousness of youth work at this time. We may not always agree with each other but by working through and across those borders or boundaries that divide us, we can find new ways of understanding the world and reimagining new possibilities for, as yet, unknown futures. In doing so, our aim is to contribute to a vibrant and socially just practice that is sustainable and vital in a post-Brexit Europe.

Conclusion

The concerns outlined here about the potential impact of Brexit on youth work are, at this uncertain moment in time, somewhat speculative possibilities. As yet, exit negotiations are not finalised and initial talks appear fragmented. It may be some time before attention turns towards the future contribution and funding of youth work. In this light, the challenges of exiting the EU are unknown and untested. So, we believe that the most positive and useful approach is to embrace this moment or ‘tipping point’, in order to reconsider and reimagine how youth work, and youth workers, might work towards developing new forms of practice. Set within a narrative of transformational creativity, it may be possible to establish a new or alternative discourse as a counterbalance to the very real fears, exceptional conditions and inherent uncertainties, which a series of public sector cuts have brought to an already hard-pressed workforce (many of whom give their time voluntarily).

An alternative discourse is required, but at this stage, the conversation about Brexit has not been collectively established in youth work or among youth workers. Having spoken with youth workers in Scotland, Northern Ireland, and with colleagues teaching youth and community work across the UK, we hear that such conversations are at best, ad hoc, and, at worst, are actively discouraged or blocked by line managers who are fearful of politicising practice. Further, the kind of re-imagined youth work that is necessary for a successful Scotland, and for the rest of the UK, in the post-Brexit era is also unknown. This raises a question around the extent to which we, as practitioners, and the young people we work alongside, can begin to help shape that unknown future, if we do not engage, or are prevented from engaging, in such conversations. Yet, our initial examination of what is already known, combined with the application of logic, can offer insights into the financial and other impacts of Brexit on youth work provision. Missing from this analysis is a robust understanding of the views and capacities of a committed workforce, who offer a high social return on investment, for a renewed creative, resilient and strong youth work sector both inside the UK and across Europe.

The ‘doom-and-gloom’ scenario is not without substance as cuts take effect. Yet, the creative possibilities that this tipping point brings, have still to be fully explored and their impacts considered. We believe there is an urgent need for a creative and forward-facing dialogue between, and with, youth workers and young people engaged in youth work, that responds to current Brexit discussions. Rather than becoming consumed or driven by a reaction that is grounded in uncertainty and fear of the unknown, additional research and space for dialogue in this area could fill the void and help to ensure that the youth work sector is adequately prepared for whatever Brexit negotiations may bring. As such, we end on an optimistic note, where practitioners may be galvanised in taking forward this dialogue in order to ensure that, when the time comes, we are resilient and clear as to our purpose and position within a post-Brexit European youth work sector that asserts a refreshed social and democratic purpose for emancipatory practice.

Youth & Policy is run voluntarily on a non-profit basis. If you would like to support our work, you can donate below.

Last Updated: 26 October 2017

Acknowledgements:

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Emily Beever and Liz Green of YouthLink Scotland who initiated this piece of work.

References:

Bauman, Z. (2012) Liquid Modernity. (2nd ed). Cambridge, Polity Press with Oxford, Blackwell.

Bauman, Z. (2000) Liquid Modernity. Cambridge, Polity Press with Oxford, Blackwell.

Beever, E. and Green, E. (2017) Unpublished Summary Report: The impact of leaving the EU on the youth work sector. Edinburgh, YouthLink.

Bruter, M. and Harrison, S. (2016) Did Young People bother to vote in the EU Referendum? Retrieved, January 12, 2017, from http://www.ecrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Did-young-people-bother-to-vote-in-the-EU-referendum.docx

Coburn A. (2011) Building social and cultural capital through learning about equality in youth work. Journal of Youth Studies (14) (4) 475-499.

Coburn, A. and Gormally, S. (2017) Communities for Social Change: Practising Equality and Social Justice in Youth and Community Work. New York, Peter Lang.

Coburn, A. and Wallace, D. (2011) Youth Work in Communities and Schools. Edinburgh: Dunedin Press.

European Commission (2001) A New Impetus for Youth, White Paper. Retrieved February 10, 2017, from https://www.erasmusplus.org.uk/file/273/download

European Commission (2014). Working with Young People: the value of youth work in the European Union. Retrieved January 14, 2017, from http://ec.europa.eu/assets/eac/youth/library/study/youth-work-report_en.pdf

European Union (2009). An EU Strategy for Youth – Investing and Empowering: A renewed open method of coordination to address youth challenges and opportunities. Retrieved August 6, 2011, from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2009:0200:FIN:EN:PDF

Gladwell, M. (2000) The Tipping Point: how little things can make a big difference. Back Bay, Little Brown Books.

Hall Aitken (2016) Social and economic value of youth work in Scotland: initial assessment report. Retrieved, February 14, 2017, from http://www.youthlinkscotland.org/index.asp?MainID=21159

Helm, T. (2016) July 2 Poll reveals young remain voters reduced to tears by Brexit result. The Guardian, Retrieved February 1, 2017, from https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jul/02/brexit-referendum-voters-survey

Hughes, G., Cooper, C., Gormally, S. and Rippingale, J. (2014) The state of youth work in austerity England – reclaiming the ability to ‘care’, Youth & Policy, Retrieved February 8, 2017, from https://www.youthandpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/yandp113.pdf

Mayne, J. (2012) Contribution Analysis: Coming of Age? Evaluation, 18, 270-295.

Moore, P. (2016) How Britain Voted, Retrieved, February 1, 2017 from https://yougov.co.uk/news/2016/06/27/how-britain-voted/

Scottish Government (2013) The Requirements for Community Learning and Development (Scotland) 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2017, from http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ssi/2013/175/pdfs/ssi_20130175_en.pdf

Scottish Government (2015) Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act. 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2017, from http://www.gov.scot/Topics/People/engage/CommEmpowerBill

Standing, G. (2011) The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. London, Bloomsbury.

Unison (2016a) A Future at Risk: Cuts in Youth Services. Retrieved February 5, 2017, from https://www.unison.org.uk/content/uploads/2016/08/23996.pdf

Unison (2016b) Growing Pains: A survey of youth workers. Retrieved February 5, 2017, from http://www.unison-scotland.org/library/20160509-Youth-Work-Damage-Series2.pdf

Wenger, E. (1998) Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

YouthLink Scotland(2014) National Youth Work Strategy 2014-19. Retrieved February 1, 2017, from, http://www.youthlinkscotland.org/Index.asp?MainID=19180&UserID=1479

Biography:

Dr. Sinéad Gormally is a senior lecturer at the University of Glasgow and Dr. Annette Coburn is a lecturer at the University of the West of Scotland. Working collaboratively, Annette and Sinéad’s youth and community work research interests are focused on creating praxis in striving for a more socially just society.