Article: Young people need youth clubs. A needs analysis in a London borough

In this article, Naomi Thompson and David Woodger outline the findings of a needs analysis relating to young people, conducted with 426 young people, parents and professionals in a London borough. The findings support a case for open access youth work and some targeted support, with ‘crime and safety’ and ‘mental health and wellbeing’ identified as young people's most pressing needs. Despite mental health being identified as a prevalent need, respondents did not overwhelmingly identify individual counselling as a key service needed. Youth clubs were identified as the most needed service, followed by targeted support around crime. This suggests universal youth work and other group activity is seen as the most appropriate response to young people’s needs.

This article outlines the findings of a needs survey that was conducted in a London borough by academic researchers on behalf of its main youth service provider. The needs analysis was commissioned by the Youth Service in 2018 as part of its future planning. The survey was designed to assess what local stakeholders including young people, parents and professionals saw as the most pressing needs facing young people in the borough and the forms of youth provision that were needed. It was responded to by a diverse range of young people, parents and professionals from across the borough. A diverse range of ages, gender, and ethnic groups were represented in the sample, reflecting the borough’s diverse profile.

According to the 2011 census the population size in the borough was 275,900 with 0-19 year olds making up 70,100 of this total (ONS, 2012). The census data showed 47% of the borough’s population as from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups. Black African and Black Caribbean (each at just over 11%) were the highest groups after White British and the proportion of ‘White other’ among the White groups had increased since the previous Census. 160 different languages were spoken in the borough and the proportion of BAME groups was much higher among young people than the all-age population (ONS, 2012). The Index of Multiple Deprivation (2015) placed the borough in the top 20% most deprived local authorities nationally with poverty levels just below the London average (MHCLG, 2015), with areas of deprivation and affluence in close proximity to each other.

Overall, the needs analysis survey we conducted in the borough found that among respondents there was a strong emphasis on youth clubs as the most important form of youth provision. Alongside this, young people, parents and professionals wanted to see specialist crime prevention programmes. ‘Crime and safety’ and ‘mental health and wellbeing’ were identified as the most pressing needs facing young people in the borough. Respondents overwhelmingly felt that local and national government should be the primary funder of youth services. Reflecting the fact that youth services are operating in a challenging financial climate, more than half of respondents felt that there was not enough youth provision in the borough.

The main youth service provider in the borough ceased to be managed by the local authority in 2016 but currently still receives the bulk of its funding from the local authority. The Youth Service currently has 14 sites across the borough and engages with 5,000 young people per year. It works with those aged 8-19 (and up to 25 with additional needs). The main focus of the Youth Service is on maintaining universal, open access provision.

Over the last couple of decades, both prior to and during the austerity era, many UK youth work practitioners and scholars have championed open access youth work and mourned its decline (see, for example: In Defence of Youth Work, 2009; de St Croix, 2016). Several scholars have raised critiques of the more restricted, targeted, short-term and outcome-based provision (Stanton, 2004; Davies, Taylor & Thompson, 2015; de St Croix, 2017; Taylor, 2017; Davies, 2019). They have recognised that the threats to these more open forms of youth work are not just post-recession funding cuts but broader ideological threats linked to the neoliberal era such as capitalism, marketisation and the impact measurement agenda (Davies, 2013; de St Croix, 2018; McGimpsey, 2018; Taylor, 2017).

Whose needs were considered?

The needs analysis was conducted via a quantitative survey. A total of 426 people responded to the survey. 199 respondents were young people. 111 respondents were parents. 116 were professionals working with young people in the borough including teachers, youth workers, social workers, police, community workers and a wide range of other professionals.

Of the young people who responded to the survey, 37% were aged between 8 and 11; 40% were aged between 12 and 15; and 23% were aged between 16 and 19. 60% of the survey respondents were female, 39% were male and 1% identified as non-binary. Of the young people who responded, 51.5% were female, 48% were male and 0.5% was non-binary. In terms of ethnicity, the surveys’ respondents represented the borough’s diverse profile: 42% of respondents identified as Black, 5% as Asian, 13% from mixed ethnic backgrounds, 35% as White and 5% as other ethnic groups. Of the young people who responded, 77% were from BAME groups.

The survey was designed by the researchers, but disseminated by the local Youth Service. Their intention was to reach people who were not currently accessing youth services in the borough alongside those who were. Therefore, the main source of dissemination was through schools and other organisations working with young people. However, after the first few weeks, while parents and professionals had responded to the survey, the number of young people’s responses was very low. As such, the Youth Service had to largely use their own networks of provision to access young people to complete the survey. Whilst most of the borough’s 18 wards were represented among the responses, the majority of young people and parents who responded were from 5 wards in particular; these being areas where key youth service provision is based. 97% of the young people aged 8-19 who responded were aware of the local Youth Service’s provision. 90% of the young people who responded stated that they access this provision. This demonstrates that the survey primarily reached young people who are already accessing youth services. This is likely to have affected their responses as to the need for such provision.

Analysis of need

When respondents were asked which needs young people face, a broad range was identified.

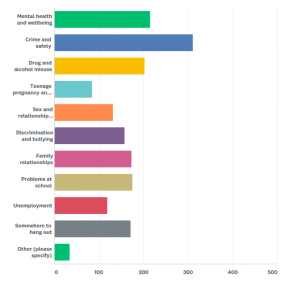

Figure 1: range of needs identified by respondents

The percentage of respondents who identified each need was as follows (respondents could choose multiple categories therefore the total amounts to more than 100%):

- 79% of respondents identified ‘crime and safety’ as a key area of need facing young people.

- 55% identified ‘mental health and wellbeing as a key area of need.

- 51% identified ‘drug and alcohol misuse’ as a key area of need.

- 44% identified ‘problems at school’ as a key area of need.

- 44% identified ‘family relationships’ as a key area of need.

- 43% identified ‘somewhere to hang out’ as a key area of need.

- 40% identified ‘discrimination and bullying’ as a key area of need.

- 33% identified ‘sex and relationships education’ as a key area of need.

- 30% identified ‘unemployment’ as a key area of need.

- 21% identified ‘teenage pregnancy and young parenthood’ as a key area of need.

- 9% specified other needs including housing, poverty, social media, disability and domestic abuse.

This indicates that young people, parents and practitioners identified young people as facing a wide range of needs that youth services might respond to. However, when they were asked to identify the one most pressing need that young people face, a starker distinction between these different needs occurred.

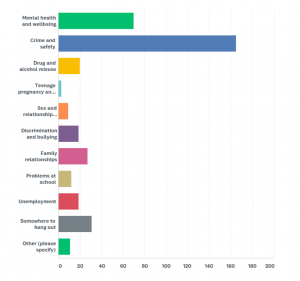

Figure 2: the one most pressing need, as identified by respondents

It can be observed here that ‘crime and safety’ was viewed as the most pressing need (43%) followed by ‘mental health and wellbeing’ (18%). All other needs were only identified as most pressing by between 1% and 8% of respondents. ‘Crime and safety’ was identified as the most pressing need by young people, parents and professionals – but especially so by young people,of whom 52% believed this to be the most pressing need. For young people from BAME backgrounds, this was slightly higher again at 54%. More parents and practitioners than young people identified ‘mental health and wellbeing’ as the most pressing need (24% of parents and 25% of professionals compared with 11% of young people). When broken down according to the different age groups of young people, fewer than 50% of 8-11 year olds saw ‘crime and safety’ as the most pressing need (44%) whilst more than 50% of the older age groups ranked this need the highest (56% of 12-15s and 51% of 16-19s). Those aged between 8 and 11 did not see ‘mental health and wellbeing’ as being as significant as the older age groups.

Responses to questions around the types of youth provision that are needed offered an indication of how respondents felt these needs may be addressed. When asked to identify what provision was needed, respondents identified a broad range.

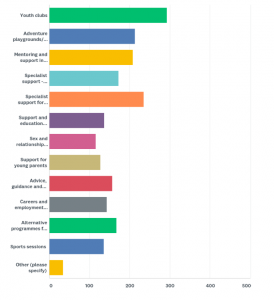

Figure 3: range of provision needed, as identified by respondents

The needs identified were as follows (respondents could choose multiple categories):

- 74% of respondents identified ‘youth clubs’ as a form of youth service that is needed.

- 59% identified ‘specialist support for young people at risk of or engaged with crime, violence and/or gangs’ as a form of youth service that is needed.

- 54% identified ‘adventure playgrounds/outdoor activities’ as a form of youth service that is needed.

- 53% identified ‘mentoring and support in schools’ as a form of youth service that is needed.

- Between 29% and 44% of respondents identified each of the other categories of provision as needed.

- 9% of respondents suggested other forms of provision they felt were needed including music, arts and creative activities, and support for young people with educational needs or disabilities.

Youth clubs rated higher than all other forms of provision. When asked to identify the one form of provision that respondents felt was most needed, the distinctions in priority were even more stark.

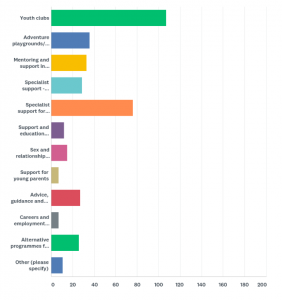

Figure 4: the one most needed form of provision, as identified by respondents

28% of respondents identified ‘youth clubs’ as the most needed form of youth provision. 20% identified ‘specialist support for young people at risk of, or engaged with crime, violence and/or gangs’ as the most needed form of youth provision. All other forms of provision were identified by between 2% and 9% of respondents as the most needed. It is significant that both ‘advice, guidance and counselling’ and ‘specialist support – mental health and wellbeing’ were only chosen by 6% and 8% of respondents as the most needed service despite ‘mental health and wellbeing’ being the second highest identified need (although taken together, this potentially accounts for 14% of respondents identifying specialist mental health provision as most needed). Overall, the data suggests that respondents didn’t necessarily see these particular services as the most appropriate response to mental health needs but that the provision of youth clubs and group activity may be more crucial. It may also indicate that they viewed different needs, such as ‘crime and safety’ and ‘mental health and wellbeing’ as interlinked and requiring a coordinated response rather than disparate mental health services being needed.

When broken down according to the different groups of respondents, young people were most likely to feel that ‘youth clubs’ were the most needed provision with 31% of young people, 24% of parents and 25% of professionals identifying them as the most needed. Parents and professionals were more likely than young people to state that specialist support relating to crime was most needed, with 17% of young people, 21% of parents and 23% of professionals choosing this category. Young people who were female or from ethnic minority groups were slightly more likely to identify specialist support relating to crime as the most needed provision than young people generally with 21% of young women and 19% of BAME young people choosing this category. When broken down by age group it can be observed that young people who were older were less likely to identify ‘youth clubs’ as the most needed provision. Only 23% of 16-19 year olds chose this category compared with 40% of 8-11 year olds and 32% of 12-15 year olds. 20% of 16-19 year olds identified specialist support relating to crime as the most needed provision compared with 17% of each of the other age groups.

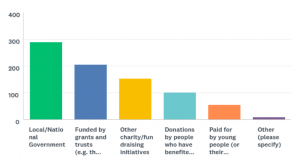

Respondents were also asked about how they thought youth services should be paid for.

Figure 5: how respondents thought youth services should be funded

There was overwhelming support for services to be paid for primarily by local/national government across young people, parents and professionals (82%) as well as substantial support for it to be funded by grants and trusts (58%) and other charity funding (43%). 29% of respondents thought that youth services should be paid for through donations from people who have benefited from services and 16% of respondents thought they should be paid for by young people (or their parents) who are accessing the services (these percentages total more than 100% because respondents could choose multiple categories). 16% of young people, 19% of parents and 12% of professionals indicated that one way that services could be paid for was through charging the young people accessing the services or their parents. Among the young people, 16-19 year olds were the least likely to suggest that services could be paid for at the point of access. 8-11 year olds were the most likely to suggest they could be paid for in this way. Whilst this was the least popular option, it suggests that some young people and parents may be willing to pay for provision. However, this needs to be couched in the recognition that very few young people and parents were suggesting they could or would pay for provision; and the support for this from professionals was even lower. Charging for provision, even with some means testing or alternatives, could create feelings of exclusion and stigma, and access and inclusion issues need to be considered especially for families living in poverty. When asked if there was enough youth provision in the borough, 54% of respondents felt there was not enough youth provision, 24% felt there was the right amount of provision and 21% were not sure. Nobody felt there was too much.

Implications

The survey findings offer clear implications for the types of need that stakeholders think exist for young people and what provision might address these needs. It also offers some implications as to how such provision might be funded. Respondents felt that local and national government should be the main funders of youth services. This supports a case for local authority funding for core work in youth clubs with some programmes or facilities potentially supplemented by grants from trusts and charities. Based on the responses around funding, there is clear overall support for youth services to be free at the point of access for young people.

A broad range of needs were identified and in an ideal scenario, a wide range of needs-based provision would be offered by youth services. In the London borough in which our analysis took place, the most pressing needs identified related to crime prevention and mental health and the most needed provision was identified as youth clubs followed by specialist support for young people engaged in or at risk of crime, violence and gangs.

Specialist support is not necessarily separate from youth club provision as it can be offered as part of a youth club’s programme of activities. However, it can also be offered in other ways such as through detached youth work, in-school, and through targeted, referral-based programmes for those with the highest support needs. There is a call to consider what mental health provision is needed as mental health was identified as a pressing need. Counselling and specialist mental health support, however, were not identified as the appropriate response when asked about the most needed provision. It may be that group support and mentoring within youth clubs and potentially within schools are more relevant forums for responding to this need for the young people. Further qualitative research could add nuance as to how people think the mental health needs young people face can be addressed through youth services. There are also questions to be raised about why specialist mental health services were not favoured by respondents. Firstly, whether the impact of funding cuts to the mental health sector is such that services are no longer accessible or suitable for young people, rather than them not being needed. Secondly, whether certain groups of young people are less likely to trust and want to access these services, particularly those from minority ethnic groups.

Despite ‘crime and safety’ being identified as the highest need, youth clubs were highlighted as the most needed provision by young people, parents and professionals rather than targeted interventions. This supports an argument that people appear to be in support of open access youth work as the most important provision for young people. However, some qualitative research would be helpful in exploring this further. More research is also needed with young people who do not currently access youth services as well as further quantitative and qualitative research beyond one London borough.

Overall, whilst recognising the need for this broader research, we draw some tentative implications for the future of youth work in London and beyond from this study. These being that young people, parents and professionals support the need for youth work and a properly funded Youth Service as the response to a range of young people’s needs including crime, safety, mental health and their broader wellbeing. Open access youth work appears to be championed over targeted services as the key form of youth provision needed.

Youth & Policy is run voluntarily on a non-profit basis. If you would like to support our work, you can donate any amount using the button below.

Last Updated: 26 May 2020

References:

Davies, B. (2013) Youth Work in a changing policy landscape. Youth & Policy No. 110, 6-32.

Davies, B., Taylor, T. and Thompson, N. (2015) Informal Education, Youth Work and Youth Development: Responding to the Brathay case study, Youth & Policy, No. 115, 85-110.

Davies, B. (2019) Austerity, Youth Policy and the Deconstruction of the Youth Service in England. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

de St Croix (2016) Grassroots youth work: policy, passion and resistance in practice. Bristol: Policy Press.

de St Croix, T. (2017) Time to say goodbye to the National Citizens Service? Youth & Policy https://www.youthandpolicy.org/articles/time-to-say-goodbye-ncs/.

de St Croix, T. (2018) Youth work, performativity and the new youth impact agenda: getting paid for numbers?, Journal of Education Policy, 33:3, 414-438.

In Defence of Youth Work (2009) The Open Letter https://indefenceofyouthwork.com/the-in-defence-of-youth-work-letter-2/.

ONS (2012) Census 2011. Office for National Statistics https://www.ons.gov.uk/census/2011census/censusanalysisindex.

McGimpsey, I. (2018) The new youth sector assemblage: reforming youth provision through a finance capital imaginary, Journal of Education Policy, 33:2, 226-242.

MHCLG (2015) Index of Multiple Deprivation 2015, London: Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2015.

Stanton, N. (2004) The youth work curriculum and the abandonment of informal education. Youth & Policy, No. 85, 71-86.

Taylor, T. (2017) Treasuring, but not measuring: personal and social development. Youth & Policy. https://www.youthandpolicy.org/articles/treasuring-not-measuring/.

Biography:

Naomi Thompson and David Woodger both lecture and research youth and community work at Goldsmiths, University of London