Article: Practice makes Perfect? Digital youth work in Flanders-Belgium

In this article, Lotte Vermeire, Wendy Van den Broeck, Fazlyn Petersen, Leo Van Audenhove & Ilse Mariën explore the possibilities of digital youth work, in Flanders Belgium; highlighting the role of digital literacy, and policy recommendations for implementing digital youth work.

Introduction

Society has been characterised by the digitalisation of its different sectors (Perez, 2009), leading to the need for new digital competences amongst the population, such as using, producing, and understanding media. These competences can be developed at school, but also in more non- and informal settings[1] (Meyers et al., 2013; Nygren et al., 2019), such as digital youth work. While the European Union’s policy pays great attention to the possibilities offered by youth work and non-formal learning, they also state that this setting needs to be further investigated (Council of the European Commission, 2009; 2012). Consequently, this paper looks into the role of digital non-formal education in Flanders-Belgium[2]. We delve deeper into the possibilities these initiatives offer to improve young people’s (digital) competences, the role of policy in organising inclusive digital youth work, and the different opportunities and challenges that arise when implementing digital youth work. The paper starts by defining digital youth work’s connection to education, then details the study’s methodology, discusses the most important findings, and closes with policy recommendations.

Digital youth work as non-formal learning

In many European member states, youth work often implies youth welfare work. This is only to a lesser extent the case in Flanders. Flanders distinguishes between youth work and youth welfare, considering them as two distinct categories within the youth sector. The Flemish government defines youth work as,

“sociocultural work based on non-commercial objectives for or by youth […], in leisure time, under educational guidance and to promote [their] general and integral development” (Vlaamse Overheid, 2012, p.14117).

It has a large emphasis on recreation, emancipation, and empowerment, and is used less as a means of counselling (Van der Eecken et al., 2017). Flemish youth work benefits from substantial government support, providing a strong foundation for its initiatives. There are also dedicated support structures in place that play a crucial role in facilitating and coordinating youth work, and Flemish youth work has a high level of voluntary involvement, highlighting the active participation of volunteers in shaping and delivering youth practices.

Nevertheless, youth work in Europe also has many commonalities with youth work in Flanders. Youth work is about creating space for young people, but it also serves to link the younger generation with education, employment, and meaningful engagement and inclusion in society (Council of Europe, 2017). This bridge function also extends to societal innovations, such as digitalisation. Digital media is not only an integral part of young people’s lives but also of society at large. Therefore, digital youth work has a significant role, which is why it was put on the European policy agenda in 2019:

“Digital youth work can be defined as ‘proactively using or addressing digital media and technology in youth work. […] [D]igital youth work can be included in any youth work setting […]. [It] can happen in face-to-face situations as well as in online environments – or in a mixture of these two. Digital media and technology can be a tool, activity, or content in youth work” (European Commission, 2019, p.6).

Based on the abovementioned definition, it is made clear that digital youth work entails youth work where digital media/technology is featured and/or discussed. Activities then do not necessarily need to entail actively working with digital tools/platforms, such as coding, but also focus on, for instance, discussing the challenges of social media. What it, however, always includes, is an educational aspect where young people get the chance to work on their personal development in a non-formal environment. In that sense, it can be an asset for improving digital competences.

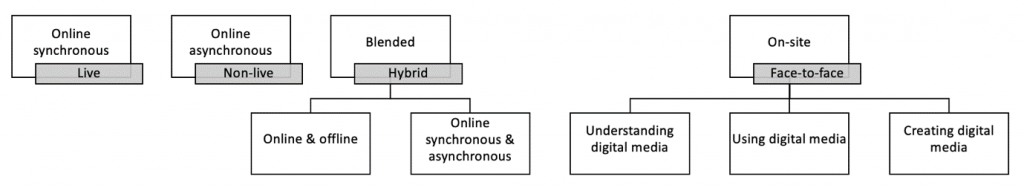

Drawing from Arkorful & Abaidoo’s (2014) e-learning model (in which they distinguish adjunct, blended, and wholly online), we identified four primary categories of Flemish digital youth work based on the way activities are organised (Vermeire et al., 2022). The classification of digital initiatives is further explained below:

Figure 1. Types of digital youth work (Vermeire et al., 2022)

Online synchronous entails a real-time interaction, where both participants and facilitators are engaged online at the same time, for example, an online live quiz or livestream.

Online asynchronous is non-live, where participants and facilitators engage separately online, for example, a peer-to-peer discussion forum or fulfilling offline challenges set by the youth workers and sharing the results online.

Blended is a hybrid approach that either combines both online and offline components or integrates live and non-live elements. For instance, a Discord channel could host live activities and also include non-live elements. Additionally, on-site holiday camps might incorporate an online module.

On-site practices focus on engaging with digital media in several ways:

- Utilising digital media, g. in a medialab.

- Creating digital media, g. a coding game or recording a podcast.

- Adopting a critical perspective and focussing on understanding digital media, g., a media literacy game to learn about cyberbullying or sexting (Vermeire et al., 2022).

Through youth work, young people who are normally digitally excluded can be included, not only by getting access to hardware provided by the youth workers but also by being able to develop their competences at their own pace. This is also indicated by other researchers, such as in the work of Erich (2018), who stresses the importance of accessible, local libraries, or Ravenscroft (2020), who states that their participatory radio creation project – in which young people are guided to create their own radio shows – supports non-formal learning for and empowerment of disadvantaged youth.

“Adopting […] interventions that emphasise fostering this confidence, motivation, and voice could be the ‘key’ that opens the door to further instrumental learning for socially excluded young people” (Ravenscroft, 2020, p.15).

Regarding the policy in Flanders, digital youth work has not yet been included in the youth work decrees, therefore, the current regulations still focus on physical activities (Vermeire et al., 2022).

Methodology

We applied an in-depth case study analysis of 12 successful Flemish digital youth work cases. Semi-structured online interviews with representatives of each case took place between October and November 2021. The interviews took place online and the researcher ensured adjusted interview techniques, comparable to those of Heiselberg and Stępińska (2022), such as providing visual listening cues, activation through validation, and creating a good mutual understanding. Using open questions, the interviewees elaborate on the topics of capacity-building, sustainability, accessibility and inclusion, digital competences, and the influence of the covid-19-crisis. Consequently, this allowed us to identify the different principles of Flemish digital youth work and make it clear to policymakers and the youth work sector how the cases were designed, what challenges they faced, and how they responded to them. This enhances scalability and transferability.

Findings

During the interviews, respondents often touched on the same topics, such as the importance of accessibility and the need for strong partnerships. In this discussion, three main aspects are highlighted:

- The definition and scope of digital youth work.

- The accessibility and inclusion of a practice.

- The competences of youth and youth workers.

Related to these aspects, several challenges and opportunities were noted. The challenges create obstacles to organising sustainable and inclusive digital youth work, but the best practices also indicate many possibilities. These three aspects require more attention from the youth sector if they wish to create and support digital youth work that increases the digital competences of its participants.

First, the meaning and extent of Flemish digital youth work needs to be clearly defined. During the interviews, the respondents advocated for more clear regulations. Several organisations indicate that there is a need for a unified definition, an overview of available tools and support, and an overview of good practices. This would also allow organisations to explore what partnerships are possible and to consult the offerings regarding the capacity-building of youth workers.

Second, interviewees emphasised the importance of ensuring access to material/devices. Most encountered challenges in implementing accessible practices, recognising that their target group might not possess a laptop or have access to a stable internet connection. Consequently, they established inclusive approaches through trial and error. Additionally, a handful of organisations noted that they leveraged the covid-19 crisis as a ‘trial period’ to assess effective strategies for digital inclusivity within their group. When talking about digital competences, one must discuss digital inclusion, because accessibility of material is only one of the aspects important to tackle. It is not enough to merely provide hard-/software, there must also be sufficient competences.

Therefore, third, attention must be paid to the digital competences of the participating young people. Several respondents mentioned that young people are not always as competent as they are expected to be, e.g., information skills. This is substantiated by the recent Flemish study Apestaartjaren (Vanwynsberghe et al., 2022) on young people and the digital world. Prensky’s (2001, p.1) idea of ‘digital natives’, which states that young people are ‘native speakers of the digital language’, has been refuted by various sources. Flemish youth work aims to be inclusive, which means that not every participant can be expected to have the necessary access or competences (Mariën & Brotcorne, 2020). In addition, several respondents indicated the need to focus on internal and external knowledge-sharing for youth workers, who also do not necessarily possess digital competences. Through sharing, organisations learn about other tools, platforms, and target groups. The case studies highlight partnership as a success criterium. Most of the good practices have established a collaboration with other organisations to build on each other’s expertise, benefitting young people thanks to the quality of the practices and paying attention to their specific needs. Several initiatives also asked for input from young people to better adapt the practice to the participants’ needs, so youth workers worked with the feedback and conclusions from participants to improve their operations.

Discussion and recommendations

The best practices indicate (policy) recommendations for the abovementioned aspects. Working on these specific elements aid the successful implementation of digital youth work, and thus the possibility to improve young people’s digital competences.

As stated above, the first recommendation refers to the importance of accurately defining digital youth work and the need for information in establishing digital initiatives. Consequently, a well-developed framework could guarantee that organisations have a clear understanding of the concept of digital youth work, along with its role within the youth field. For instance, organisations indicate its potential benefits, such as engaging frequently excluded demographics or improving media literacy. In addition, it is also important that organisations commit to a framework within their activities, e.g., a code of ethics.

The second recommendation pays attention to the digital competences of youth workers. As mentioned above, merely providing hard-/software is not adequate. Youth workers must also be able to adequately coach participants. It should not be expected that youth workers are digital experts, nonetheless, they should be able to offer appropriate, tailored support. This is important both in terms of understanding and using digital media, such as being aware of the challenges young people face online. If they possess proper digital competences, they are the ideal person to train and support young people in an approachable and trustworthy way.

The case studies show that youth workers have made a tremendous effort to teach themselves the necessary digital competences, by looking things up, trying things out, and asking for help from others, all to implement their practice in the best feasible way. However, there is an argument for integrating digital youth work in a low-threshold, but mandatory training program. In Flanders, volunteers have to follow a training course to become ‘instructors’. This is not the case for professional youth workers in Flanders, who often already have a college/university degree. Respondents mention that a low-threshold, applied course that pays attention to the digital aspects of youth work should be made available. Earlier research shows that youth workers must have access to professional training to provide qualitative practices (Borden et al., 2004).

Youth workers feel inadequate to help improve the digital competences of young people, mainly because they are insecure and experience anxiety about their digital competences, something that was also noted by Pawluczuk et al. (2019). Youth workers feel there are not enough affordable and short-term training options to improve digital literacy. Similar results were found in other European studies, such as the Skill IT-study on youth work in Ireland, Norway, Poland, and Romania. Skill IT concludes that ‘[…] many of the staff or volunteers who work with young people lack confidence, feel inadequately equipped to use digital technology with them’ (Skill IT, 2020, p.5).

The last recommendation notes the possibilities of education through digital youth work. Several respondents noted the added value of ‘learning-by-doing’, or active learning. Here, the focus is on participation and for-and-by youth, where participants are at the helm of their learning and even co-create practices, e.g., putting together a working group to provide feedback, thus making sure the initiative pays attention to young people’s needs. Youth workers are in a strong position to help young people navigate and acquire the right competences to deal with the digital world. Activities based on playful learning, and peer-to-peer activities where young people take responsibility and work together, are motivating and effective.

As mentioned above, youth work strives to empower and equip young people for social integration and engagement in society. With a significant portion of our daily activities now occurring online, digital literacy is essential for tasks like job applications or doing our finances. In this context, digital youth work aligns with the principles of regular youth work. It offers opportunities, such as overcoming distance and fostering critical digital competences, but it also presents challenges. Key barriers include a lack of necessary expertise among youth workers, potential digital exclusion, especially for vulnerable youth, and constraints tied to required hardware, software, and internet access. Additionally, not all activities require a digital element, as young people also require real-life interaction, and necessary face-to-face support or training.

Conclusion

Our research highlights three key areas for non-formal education policies, namely (1) clearly defining and communicating digital youth work, (2) promoting attention to digital inclusion and accessibility, and (3) enhancing the digital literacy and capacity of youth and youth workers. Digital literacy is essential for (pro)active societal participation, but the lack of a clear definition for digital youth work creates confusion. Policymakers are advised to create a consultable, visionary document that defines digital youth work and provides guidelines and best practice examples. Additionally, the shift to digital youth work requires reflection on digital inclusion. The digital inclusion field and its various actions are unknown to most youth organisations, so knowledge-sharing activities are a requirement, as is attention to capacity-building of youth organisations, such as providing training on quality digital youth work. Encouraging co-creation with young people in shaping activities will further improve the inclusiveness and effectiveness of a practice.

Youth & Policy is run voluntarily on a non-profit basis. If you would like to support our work, you can donate any amount using the button below.

Last Updated: 13 March 2024

Footnotes:

[1] Memorandum of Lifelong Learning (European Commission, 2000) distinguishes three types of learning, namely formal, non-formal and informal. The European Commission describes formal learning as formal education. Informal learning refers to the daily events that cause a person to learn. Non-formal learning falls between these two forms and consists of learning embedded in activities not necessarily indicated as a form of learning, but which do pay attention to this, such as recreational activities for young people (European Commission, 2000).

[2] Dutch speaking part of Belgium.

Additional information

Interview in English on digital youth work: What remains of the joy of experimentation? Digitalisation is changing youth work

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to all those involved with the digital youth work in Flanders project.

References:

Arkorful, V. and Abaidoo, N. (2014). The Role of e-Learning, the Advantages and Disadvantages of Its Adoption in Higher Education. International Journal of Education and Research, 2, 397-410.

Borden, L., Craig, D., & Villarruel, F. (2004). Professionalizing youth development: The role of higher education. New Directions for Youth Development, 104, 75-85. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.100

Council of Europe. (2017). Recommendation CM/Rec(2017)4 of the Committee of Ministers to member States on youth work. https://rm.coe.int/0900001680717e78

Council of the European Union. (2009). COUNCIL RESOLUTION of 27 November 2009 on a renewed framework for European cooperation in the youth field (2010-2018). Official Journal of the European Union, C311, 1-11. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32009G1219(01)

Council of the European Union. (2012). COUNCIL RECOMMENDATION of 20 December 2012 on the validation of non-formal and informal learning. Official Journal of the European Union, C 398, 1-5. https://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2012:398:0001:0005:EN:PDF

Council of the European Union. (2019). Conclusions of the Council and of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States meeting within the Council on Digital Youth Work. Official Journal of the European Union, C414, 1-6. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/ad692045-1b46-11ea-8c1f-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF

Erich, A. (2018). The Role of Public Libraries in Non-Formal Learning. Romanian Journal for Multidimensional Education, 10(3), 17-24. https://doi.org/10.18662/rrem/59

European Commission. (2000). A Memorandum of Lifelong Learning. Publications Office. https://uil.unesco.org/i/doc/lifelong-learning/policies/european-communities-a-memorandum-on-lifelong-learning.pdf

European Commission. (2018). Developing digital youth work: policy recommendations, training needs and good practice examples for youth workers and decision-makers : expert group set up under the European Union Work Plan for Youth for 2016-2018. Publications Office. https://www.saltoyouth.net/downloads/toolbox_tool_download-file1744/NC0218021ENN.en.pdf

Gerring, J. (2007). Case Study Research: Principles and practices. Cambridge University Press.

Heiselberg, L., & Stępińska, A. (2022). Transforming Qualitative Interviewing Techniques for Video Conferencing Platforms. Digital Journalism, 1–12. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21670811.2022.2047083

Mariën, I. & Brotcorne, P. (2020). Barometer Digitale Inclusie. Koning Boudewijnstichting. https://en.calameo.com/read/001774295c3dbd33c7a48?authid=RvnIVmwOPSfL

Meyers, M., Erickson, I. & Small, R. (2013). Digital literacy and informal learning environments: an introduction. Learning, Media and Technology, 38(4), 355-367.

Nygren, H., Nissinen, K., Hämäläinen, R. & De Wever, B. (2019). Lifelong learning: Formal, non-formal and informal learning in the context of the use of problem-solving skills in technology-rich environments. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12807

Pawluczuk, A., Hall, H., Webster, G. and Smith, C. (2019). Digital youth work: youth workers’ balancing act between digital innovation and digital literacy insecurity. Information Research, 24(1). http://InformationR.net/ir/24-1/isic2018/isic1829.html

Perez, C. (2009). Technological revolutions and techno-economic paradigms (TOC/TUT Working Paper No. 20). The Other Canon Foundation, Norway and Tallinn University of Technology.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424816

Ravenscroft, A. (2020). Participatory internet radio (RadioActive101) as a social innovation and co-production methodology for engagement and non-formal learning amongst socially excluded young people. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26(6), 541-558. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1700312

Skill IT. (2020). Skill IT For Youth: Enhancing Youth Services’ Digital Youth Work Practice [Policy Brief]. https://digipathways.io/content/uploads/2020/01/Skill-IT-European-policy-brief.pdf

Van der Eecken, A., Caluwaerts, L. & Bradt, L. (2017). Country Sheet on Youth Work in Belgium (Flanders). Youth Partnership.

Vanwynsberghe, H., Joris, G., Waeterloos, C., Anrijs, S., Vanden Abeele, M., Ponnet, K., De Wolf, R., Van Ouytsel, J., Van Damme, K., Vissenberg, J., D’Haenens, L., Zenner, E., Peters, E., De Pauw, S., Frissen, L., Schreuer, C. (2022). Onderzoeksrapport Apestaartjaren: De digitale leefwereld van kinderen en jongeren. Gent: Mediaraven.

Vermeire, L., Van den Broeck, W., Van Audenhove, L. & Mariën, I. (2022). Digital Youth Work in Flanders: practices, challenges, and the impact of COVID-19. Seminar.net, 18(1), 1-19.

Vlaamse Overheid. (2012). Decreet houdende een vernieuwd jeugd- en kinderrechtenbeleid. Belgisch Staatsblad, C − 2012/35198, 14117-14144. http://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/mopdf/2012/03/07_1.pdf#Page37

Biography:

Lotte Vermeire is PhD researcher in communication studies at imec-SMIT, Vrije Universiteit Brussel and belongs to the Digital Inclusion & Citizen Engagement and Media, Marketing & User Experience units. She focusses on digital and data literacy, digital youth work, and digital inclusion.

Prof. Wendy Van den Broeck is senior lecturer at the Department of Communication Sciences (VUB) and heads the Media, Marketing & User Experience Unit. Her expertise relates to user research on new media, personalised media and digital practices. She co-founded ‘DataBuzz’, for which she received the KVAB science communication award.

Prof. Leo Van Audenhove is full professor of international communication at the VUB. He is director of the Flemish Knowledge Centre for Media Literacy and extra-ordinary professor at the University of the Western Cape. His areas of interest are media literacy, data literacy, digital inclusion and ICT4D.

Dr. Fazlyn Petersen is a Senior Information Systems Lecturer at the University of the Western Cape. Her research foci are Information Communication and Technology for Development (ICT4D) in health and education. Her research focusses on creating more inclusive online environments for students and patients, especially those with lower socioeconomic status.

Prof. Ilse Mariën has worked at imec-SMIT, Vrije Universiteit Brussel since 2007. Ilse leads the Digital Inclusion & Citizen Engagement Unit. She teaches Policy Analysis at the Department of Communication Sciences (VUB). Her research focusses on digital exclusion and inclusion, digital skills and the social impact of digitalisation.