Article: Perspectives of volunteers and professionals working County Lines

Sharlene Mills and Peter Unwin present findings from research which explored staff and volunteers' experience of working with County Lines and highlight the need for more joined up thinking.

Over recent years there has been growing concern regarding children and young people being exploited by criminal gangs who are involved in trafficking drugs and other illegal trade between different geographic locations. The recent manifestations of this phenomenon have become known as ‘County Lines’ (Home Office, 2018, p.2), a phenomenon by which gangs and organised criminal networks trade illegal drugs to across different towns and cities within the UK. Children and vulnerable adults are exploited through the dedicated use of mobile phones, coercion, intimidation, violence and weapons.

Reports such as the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for Runaway and Missing Children and Adults (2017) and the National Crime Agency (NCA) (2017) help raise awareness and highlight the dangers to children and young people, but at a practice level there has been little collation of best practice approaches. Despite these guidelines, each professional discipline and voluntary/faith organisation has their own approach to understanding and responding to the challenges of County Lines, raising questions about the efficacy of interdisciplinary safeguarding, which the present study was designed to explore.

Literature Review

Academic literature is scant in the field of County Lines (Robinson, McLean and Densley, 2018) but there is much grey literature and policy literature, which provides helpful contextual information. The NCA (2017) accessed information from 43 police forces across England and Wales, leading to a typology of County Lines, which included the following:

- A group establishes a network between an urban hub and county location, where primarily class A (heroin and crack cocaine) are supplied.

- A mobile phone line is provided with a name to be established within the market, receiving orders from introduced customers. The line is likely to be controlled by a third party who is remote from the market.

- The group exploits young or vulnerable individuals, to achieve the storage and supply of drugs and weapons, movement of money and to secure the use of dwellings (known as ‘cuckooing’).

- The group or individuals that are being exploited regularly travel between urban hubs and the county market to replenish stock and deliver money.

- The group are often inclined to use intimidation, violence and weapons.

(NCA, 2017, p.2)

Children in England are currently receiving little or no education in order to help them understand criminal exploitation and the associated risks. Most education that is provided tends to emphasise child sexual exploitation (CSE), especially after a series of national scandals had raised the public profile (e.g. Jay, 2014). CSE, which involves the grooming of children and use of false affection by adults, has some similarities with County Lines exploitation, a key difference being that County Lines exploitation has illegal commerce and money-making at its very core. County Lines gangs are being established because local, urban, drug markets are saturated by both competition and surveillance from the police (Andell, 2019). The ways in which County Lines gangs ensnare young people are explained by Andell and Pitts (2018) within the context of the wider drugs trade and its need to continually evolve. Taxi and car hire firms and fast-food outlets are also known to be providing services that facilitate County Lines (NCA, 2017), in similar ways to those experienced with CSE in the previous decade (Jay, 2014).

‘Contextual safeguarding’ (Firmin, 2017) is a term that has been developed in relation to policy and practice approaches to exploitation. Contextual safeguarding is an advanced safeguarding framework which highlights extra-familial cultural and environmental risks. it is argued that, by embracing context, professionals and volunteers have greater insight into the lived experiences of young people involved in County Lines and are thus better able to interpret dangers and trends.

The Home Office (HM Government, 2016). state they have a clear understanding of the issues and challenges involved in tackling County Lines but Ofsted, Care Quality Commission, HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and HM Inspectorate of Probation (2016) emphasise that more work needs to be done to enable professionals to have a clearer understanding of the motives of children going missing and becoming embroiled in County Lines operations.

Methodology

Ethical permission was gained from the University of Worcester for this study and gatekeeper permissions gained. Participants were afforded information prior to the study commencing and given consent forms, both of which clarified issues of confidentiality, withdrawal and dissemination issues. All interviews were conducted on a semi-structured basis and were focused on views regarding understanding of County Lines, whether County Lines was a new phenomenon, what initiatives were currently in place and how effective these were.

The emergent data was analysed using Riessman’s (1993) approach which offers standards for narrative qualitative analysis by focusing on choice of language and narrative style, sequences, and responses. The field work interviews were carried out with eight staff across a range of voluntary, statutory and faith agencies in private settings in their respective workplaces.

Findings

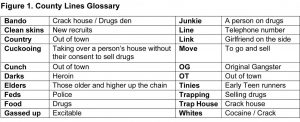

During the interviewing, it emerged that there was a whole set of jargon being used around the County lines phenomenon. Knowledge of this street language of young people is essential if young people are to best safeguarded. The front-line experience of the workers reported below led to the following ‘County Lines Glossary’ being produced:

Knowledge of such jargon is an important part of the training of all professionals involved in County Lines, the importance of cross disciplinary training having been highlighted by Williams and Finley (2018).

The following multi-agency responses are coded as follows – statutory agencies (S), voluntary agencies (V) and faith agencies (F).

Definition and Understanding

All participants positioned County Lines as another form of child exploitation, whereby involvement steals childhood, as is the situation with CSE, explained by one participant:

They just need to call it child exploitation and step away from the “sexual” and step away from the “County Lines” and just call it child exploitation and leave it as simple as that (V1)

The voluntary sector worker below explained their understanding of County Lines as:

Young people get involved with drugs and they are used to traffic drugs around the country. They are paid and they feel empowered because they’ve got the money, but … they’re the one taking the risk and the reason why I believe they use them is because they get lesser sentencing and can ride the system and get out of it much easier than if you’re an 18 or 25-year-old (V3)

It was apparent from the start of several interviews that the participants had issues with the Home Office’s (2018) definition of County Lines. Experienced professional S2 encapsulated this dilemma:

My biggest difficulty is to work out where my boundaries are and when I’ve got to call the police and when I can do something around it. To support that young person, [as opposed] to adding another offence to their record (S2)

This above finding accords with Anderson’s (2017) view that, where there is no pre-existing consensual definition on an issue, professionals adopt widely different approaches.

Multi-agency working and Interventions

Working in County Lines involves many agencies and complex moral, statutory and procedural issues, often leading to large amounts of time being spent on mutual recriminations. One participant stated:

We’ll have the school blaming the parents, community workers blaming government, parents blaming the schools. When in actual fact there’s nobody to blame because it’s just a combination of different factors (V1)

The following quotes indicated that organisations were working in isolation, with limited training and awareness, a fear of reporting children to the police and a lack of support in tackling the trauma that young people experience. Participants identified a lack of working together as characterising their experiences of County Lines work:

Silos – loads and loads and loads of silos and it doesn’t work (S1)

I’m not aware of any joined-up work (V2)

The above findings illustrate considerable dissatisfaction across the sectors with the ways in which young people and their County Lines involvement is viewed. A core question that arises is whether the young people involved are perpetrators or victims. The discussion below addresses these key issues and makes suggestions for future development.

Discussion and Conclusion

The above views on the County Lines phenomenon suggest that there is considerable disquiet about the differing approaches being taken by agencies. A core debate revolves around whether County Lines is a new phenomenon or a variation of child abuse that has been going on for many years.

The scale of County Lines, the use of social media and the glamorisation of County Lines lifestyles for some young people do seem to represent a new level and type of challenge for welfare and enforcement agencies. However, the part played by poverty, deprivation, poor education, unemployment, austerity, trauma, fear and shame also needs to be acknowledged. Workers need to be aware of the jargon used within County Lines and aware also of the part played by social media in enabling exploitation. Workers need not only to understand Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat, but also the additional platforms that young people communicate through such as GRM daily, Link up TV and SB TV that appear on YouTube featuring local rappers’ videos, some of which glamorise lifestyles otherwise seen as exploitative and degrading.

Workers involved in County Lines need to work more closely with colleagues across agencies in contextual ways which better safeguard children via developing greater levels of consensus about the causation, definitions and approaches needed to help vulnerable young people and to stem the tide of drug availability across the nation. Ways in which victims are treated initially are important, and assumptions about life-style choices should not predominate. There is clearly a role here for more shared education across statutory and voluntary agencies about the factors influencing lifestyles and choices which should help bring about more consistent and helpful approaches to the young people being exploited through County Lines.

Youth & Policy is run voluntarily on a non-profit basis. If you would like to support our work, you can donate any amount using the button below.

Last Updated: 6 April 2020

References:

Andell, J. (2019) Theory into practice. County Lines, violence and changes to drug markets Youth & Policy. 18.09.2019. Available at: https://www.youthandpolicy.org/articles/county-lines-violence-drug-markets/ (Accessed: on 14th November 2019)

Andell, J. and Pitts, J. (2018) The End of the Line? The Impact of County Lines Drug Distribution on Youth Crime in a Target Destination.12.01.2018. Youth & Policy. Available at: https://www.youthandpolicy.org/articles/the-end-of-the-line/ (Accessed on 21.09.19)

Anderson, C. (2017) Commission on Gangs and Violence: Uniting to Improve Safety. Birmingham: West Midlands Police and Crime Commissioner

All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Runaway and Missing Children and Adults (2017) Briefing report on the roundtable on children who go missing and are criminally exploited by gangs. Available at: https://www.childrenssociety.org.uk/sites/default/files/appg-missing-gangs-and-exploitation-roundtable-report.pdf (Accessed: on 14th April 2018)

Cookes, R. L, Merdian, H. L and Hassett, C. L. (2016) ‘So what about the stories? An Exploratory Study of the Definition, use, and Function of Narrative Child Sexual Exploitation Material’, Psychology, Crime and Law, 23(2), pp. 171-179. doi:10.1080/1068316X.2016.1239099

Firmin, C. (2017) Contextual Safeguarding. An overview of the operational, strategic and conceptual framework. Available at: https://contextualsafeguarding.org.uk/assets/documents/Contextual-Safeguarding-Briefing.pdf (Accessed: on 18th October 2018)

HM Government (2016) Ending gang violence and exploitation. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/491699/Ending_gang_violence_and_Exploitation_FINAL.pdf (Accessed: on 24th January 2018)

Ofsted, Care Quality Commission, HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and HM Inspectorate of Probation (2016) ‘Time to listen’: A joined up response to child sexual exploitation and missing children. London. Ofsted. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/676421/Time_to_listen_a_joined_up_response_to_child_sexual_exploitation_and_missing_children.pdf (Accessed: on 25th January 2018)

Home Office (2018) Criminal Exploitation of children and vulnerable adults: County Lines guidance. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/741194/HOCountyLinesGuidanceSept2018.pdf (Accessed: on 19th March 2018)

National Crime Agency (2017) County Lines Violence, Exploitation and Drug Supply 2017: National Briefing Report. Available at: https://www.nationalcrimeagency.gov.uk/publications/832-county-lines-violence-exploitation-and-drug-supply-2017/file (Accessed: on 19th March 2018)

Jay. A. (2014) Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Exploitation in Rotherham (1997–2013). Available at: www.rotherham.gov.uk/downloads/file/1407/independent_inquiry_cse_in_rotherham (Accessed: 27th May 2019)

Riessman, C. K. (1993) Narrative Analysis: Qualitative Research Methods. Vol 30. London: Sage Publications

Robinson, G., McLean, R. and Densley, J. (2018) Working County Lines: Child Criminal exploitation and Illicit Drug Dealing in Glasgow and Merseyside, International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, pp.1-18. doi: 10.1177/0306624X18806742

Williams, A.G. and Finlay, F. (2018) ‘County Lines: How Gang Crime is Affecting Our Young People’, Archives of Disease in Childhood, pp. 1-3. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2018-315909

Biography:

Sharlene Mills has worked for several years with young people in the criminal justice system and has recently qualified as a social worker.

Peter Unwin is a social worker, foster carer and experienced researcher keen to promote the voices of lived experience.