Article: And Someone to Talk To: The Role Of Therapeutic Youth Work

Sally Carr MBE explores the therapeutic youth work, and its significance to practice and introduces the models she has developed for practitioners. This poignant article outlines how this approach fits in with current challenges and demonstrates how youth work works effectively alongside other services such as CAHMS and Youth Justice.

We are increasingly aware of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and young people’s well-being and mental health (Young Minds, 2022); however, this story is not new. During the pre-pandemic period, youth workers actively supported young people whose well-being and mental health concerns did not meet the thresholds of support from services such as Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services( CAMHS). We now face a post-pandemic prediction that the worse is yet to come (UNICEF, 2021). So, where does youth work need to be to better support children and young people’s well-being and mental health in the near future?

Therapeutic Youth Work

This is where a conscious, deliberate and intentional Therapeutic Youth Work approach is needed. Built on the foundations of youth work ethics (Banks, 2010; IYW, 2021), youth work values (Davies, 2005) and principles (Sapin, 2013), alongside Rogers’ three core conditions of unconditional positive regard, empathy and congruence (1957), the Therapeutic Youth Work approach seeks to embed a safer and therapeutic model of working with children and young people, that is person-centred, child welfare focussed and works at the pace of the young person.

Therapeutic Youth Work is a practice. It is not a formulaic programme or project to be delivered over a set number of sessions or weeks. It is a slowed practice that is holistic. Therapeutic Youth Work tailors the activities, youth work relationships, settings and conversations to meet the needs of the young person and their peer groups. By consciously curating the approach with these considerations, the practice enables the development of a therapeutic alliance (Bordin, 1979) between the youth worker and the young person, promoting therapeutic growth and development.

Therapeutic Youth Work can support young people to lead social action projects, using a social justice approach to help young people to understand how discrimination, disadvantage and trauma impact individuals and communities. Social action projects are commonplace within youth work, and they specifically seek active change and disrupt systems that uphold intersectional discrimination and disadvantage. Here the power of resilient networks can help to unlock the power and privileges that support systemic change. Creating allies across inter-agency and partnership settings can affect cultural and systems change, reducing the risk of returning children and young people to the contexts and relationships that may have brought them to seek out our services in the first place.

It is essential to recognise where the Therapeutic Youth Work approach aligns with other frameworks, e.g. Youth Justice, CAMHS, etc. My intention for this is to support the Therapeutic Youth Work practitioner to understand where their practice connects across interagency working. Within the ‘THRIVE’ mental health and well-being framework (Wolpert et al., 2019), Therapeutic Youth Work is part of ‘Getting Advice’, ‘Getting Help’ and ‘Getting More Help’. Within youth justice and public health approaches, Therapeutic Youth Work is at the primary and secondary levels. In the Continuum of need, Therapeutic Youth Work can be used at Universal and Universal Plus. Regarding the five ways to wellbeing (NHS, 2022), Therapeutic Youth Work connects all five themes.

Therapeutic Youth Work is an integrative practice using trauma-informed (SAMHSA, 2014) and healing-centred approaches (Ginwright 2018). These approaches develop strengths in young people, enabling them to express their trauma and experience post-traumatic growth (Calhoun & Tedeschi, 2006). There should be no haste to move from trauma to healing simultaneously. Trauma is present in the body and across generations, and seeking to escalate healing in pursuing targets and outcomes can harm young people and delay post-traumatic growth.

Following several decades of youth work and youth work strategic management, I have developed a practice compass that supports the Therapeutic Youth Work practitioner’s integrative approach to supporting young people and their communities’ therapeutic growth.

The Practice Compass

Using the compass to help the Therapeutic Youth Worker to navigate their way, the practice compass is a tool that can be used to support the four key tenets of Therapeutic Youth Work, which are

- Therapeutic Relationships

- Therapeutic Environment

- Therapeutic Activities

- Therapeutic Conversations

And the conscious commitment to Healing Centred Practice. This combination enables R.E.A.C.H.

I propose that combining these through integrative practice enables ‘Therapeutic Alliance’:

Figure 1 The Practice Compass. Carr (2022)

The practice compass outlines the aspects of the integrative practice that need to be consciously considered when applying a Therapeutic Youth Work R.E.A.C.H approach.

Youth work itself has always been a practice that sought to develop young people and encourage a sense of association and belonging whilst being social and fun. Whilst young people lead the way in responding to broader and deeper global crises, such as the climate catastrophe, increased inequity and discrimination, and entrenched poverty, we need to support young people’s voice, participation, leadership and collaboration; in which hope (Bishop & Willis, 2014) is a key part of the integrative practice. Focussing on hope enables and supports young people to imagine and co-create different and better futures.

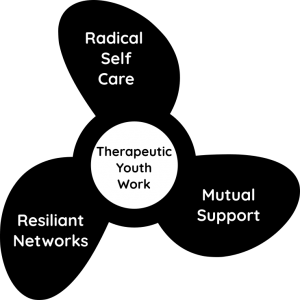

One way of operationalising hope through Therapeutic Youth Work is visualising a propeller.

Propeller model

Figure 2 – Propeller Model

The propeller model is made up of three interconnected practices. These are:

- Radical Self Care

- Mutual Support

- Resilient networks.

Radical Self Care differs from self-care in that it seeks to understand and address the causes of intersectional discrimination and intersectional disadvantage and disrupt systemic violence (TIP, 2022) rather than only treating the symptoms. Radical Self Care enhances agency in the young person by understanding systems of oppression and seeking to disrupt them.

Alongside Radical Self Care is Mutual Support, gained through the peer groups that young people choose to be part of. They are drawing on the strength and skills of other young people to develop ways to address discrimination and disadvantage together.

The third aspect is that of Resilient Networks. Resilience should not be an individual endeavour, as the continuous need for resilience in the face of adversity is exhausting and can be re-traumatising for many young people. Resilient Networks should be identified and co-created with young people to enhance support. This will help to ease toxic stress and hypervigilance (Nelson, Bhutta, Burke Harris, Danese, and Samara, 2020). The resilient networks should serve to unlock the power, status and resource for young people, their peers and their communities and support systemic change.

This is done by Therapeutic Youth Workers and young people using an interagency approach. Such an approach is used to unlock the power, status and resource needed to make systemic change by creating interagency allies. As a result, the systems that do not best serve young people can be interrupted and changed for the betterment of young people and their communities.

As we look to the future, we can see the most significant investment in Youth Work since the 1980’s coming to the sector through the Youth Investment Fund (DCMS,2022). The fund is tipped in favour of capital investment over revenue costs, and as such, this will give young people perhaps more and improved places to go and may even give an increased menu of things to do. However, we should never forget the need for someone to talk to. Healthy, safer human connections and support are vital if we want our children and young people to thrive.

And someone to talk to…

Returning to the critical question that opened this article, ‘where does youth work need to be to better support children and young people’s well-being and mental health in the near future? I suggest that we need to be journeying with young people. Utilising a sea-faring metaphor, Therapeutic Youth Work provides a practice compass to guide us, and a model to propel us. Yet, there are times when the Therapeutic Youth Worker will need to stop, drop an anchor for themselves and take time to reflect, heal and plan. Supporting the Therapeutic Youth Worker is key; ensuring dedicated supervision time with another person or a group of practitioners, where we can express and explore situations, drawing on the wisdom and insights of others to guide us. This is necessary to be the best we can be for young people. Regular supervision, keeping professional boundaries and developing a culture of safeguarding is paramount, as these will help ensure safer practice. There may be an occasion where the youth worker may need clinical supervision that offers a therapy-based lens to support them.

Examples from practice

I would like to reference two youth projects in bringing the practice to life are M13 Youth Project in Manchester and Power The Fight in London. The Sistering Project is managed by M13 and staffed by their youth workers who are community-rooted, professionally qualified women who listen carefully and respectfully and apply unconditional positive regard. These known and trusted adults are available in the young women’s community, accessible in the weekly Young Women’s Sistering Group, and at other times of the week. The project is located in a safe and accessible venue in the heart of their community and delivered in a safeguarded and boundaried way, through a weekly group meeting, phone calls, text messaging, meetups, and practical help such as accompanying a young woman to specialist services. This approach enhances the network’s resilience and seeks to reduce isolation, instead creating positive mutual community support. Young women can join the project at any time, participate at the level they feel comfortable with and leave when they want to, so they remain in control of their participation and the pace of the work.

“As a result of this, we have developed our work to take account of young women’s mental health difficulties and to work in trauma-informed ways to create a safe and welcoming environment for young women to meet in, relax, talk and engage in activities determined by them; using non-directive counselling skills to listen carefully to support young women to identify and talk about the things that concern them and to explore what action they can take.” (M13 Youth Project Manager)

At M13, the youth workers curate a psychologically safe and low-risk environment that pays attention to the specific age- and gender-related rights, lived experiences and needs of young women to enable them to control the level of information they share with each other and youth workers, building trust, and enabling deeper work through time.

“Our work is person-centred and does not judge, stigmatise or blame young women. We build self-esteem and confidence by being available to young women: in the community, in groups and one-to-one; enjoying their company, giving them our full attention and focusing on them rather than a ‘task’, helping them to identify their own positive qualities, enabling them to speak positively about themselves and others and modelling how to be a kind friend to themselves.” (M13 Youth Project Manager)

At Power The Fight, the team led by Ben Lindsey have developed the Therapeutic Intervention for Peace (TIP) approach. Power The Fight was launched as a charity in 2018 in response to the UK’s rapid increase in serious youth violence and its disproportionate impact on people from Black, Asian and Ethnically Minoritised communities. They empower and train communities to reduce risk factors, engage with government bodies for advocacy, and support bereaved families. They have developed a culturally competent therapeutic service for families and peers affected by traumatic loss.

“The pilot identified a broad variety of serious concerns children have around relationships, safety and wellbeing. School children currently have very little input or coproduction in their education which means the spaces for openly discussing their specific social concerns, anxieties and fears are often non-existent. The project found children benefit greatly from therapeutic group work that allows personal and interpersonal reflection. Art therapy and non-conventional therapeutic approaches delivered by culturally competent practitioners can produce safe, calm and transformative spaces within schools where children feel heard and understood. Therefore, a key recommendation is that schools should facilitate co-produced therapeutic and reflective spaces for children, particularly children who have been identified as having additional emotional or social needs, or those experiencing the impacts of extreme social marginalisation.” (TIP, 2021, p.5).

Both these examples emphasise the need to ensure therapeutic approaches to the practice. I argue that the relationships, environments, activities, and conversations in these practice examples created a therapeutic alliance. These elements are set at the pace of the children and young people, enabling their own goal setting and outcomes.

Conclusion

And someone to talk to… for young people having a safer, trusted and boundaried adult, outside of the home, and outside of any mandatory relationships, is vital if we are to support young people’s agency and collective action. For it is the voluntary relationship within youth work that enhances young people’s voice and supports their power and activism; The enhancement and practice of Therapeutic Youth Work take this further, supporting, and enriching, young people’s psycho-social-educational well-being. Like all good youth work, Therapeutic Youth Work is social; with fun and enjoyment being essential features of the practice

Therapeutic Youth Work, when delivered consciously and with young people’s welfare at its heart, has the potential to save and change lives. If we are to respond to the current proactively and predicted mental health crisis facing young people, then Therapeutic Youth Work provides a theoretical and practical approach. Therapeutic Youth Work safeguards young people by being trauma-informed. It develops young people through healing-centred approaches, and in doing so, enhances young people’s sense of belonging and association in the world.

Working alongside young people, Therapeutic Youth Work can identify the causes of distress, trauma and inequity faced by many young people and their communities. By supporting the individual young person’s radical self-care, alongside fostering the collective power of mutual support and resilient networks, so Therapeutic Youth Work approach can identify the systems changes that need to take place; the approaches available to make the change; and the resources necessary to support sustained transformational systemic change, that help to prevent young people continually returning to traumatic and discriminatory systems, relationships and contexts.

Youth & Policy is run voluntarily on a non-profit basis. If you would like to support our work, you can donate any amount using the button below.

Last Updated: 14 November 2022

Acknowledgements:

With thanks to Power the Fight and M13

References:

Banks, S. (2010) ‘Ethical Issues in Youth Work’, London: Routledge

Bishop, C. E., and Willis, K. (2014) ‘Without hope everything would be doom and gloom’: young people talk about the importance of hope in their lives, Journal of Youth Studies, 17:6, 778-793.

Bordin E. (1979) ‘The generalizability for the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance’. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 16:252–260.

Calhoun, L. G., & Tedeschi, R. (2006). ‘The foundations of post-traumatic growth: An expanded framework’. In L. G. Calhoun, & R. G. Tedeschi (Eds), Handbook of post-traumatic growth: Research and practice (pp. 1-23). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum

Carr, S. (2022). ‘Therapeutic Youth Work’. Available online: https://empowermentpeople.org.uk/therapeutic-youth-work/. Accessed 05.06.22

Davies, B. (2005) ‘Youth Work: A Manifesto For Our Times’, Youth & Policy, 88: 5-27.

DCMS, (2022) Youth Investment Fund. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/youth-investment-fund-phase-2-intermediary-grant-maker-competition. Accessed 05.06.22

Gatenby, H. (2021). ‘Therapeutic Youth Work’. Available online: https://empowermentpeople.org.uk/therapeutic-youth-work/. Accessed 05.06.22

Institute of Youth Work (2020). ‘Code-of-Ethics-Poster’. Available online: https://iyw.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/IYW-Code-of-Ethics-Poster-PDF.pdf .Accessed 5.12.21

Nelson, C. A., Bhutta, Z. A., Burke Harris, N., Danese, A. and Samara, M. (2020) ‘Adversity in childhood is linked to mental and physical health throughout life’. British Medical Journal 371

NHS (2019). ‘5 steps to wellbeing’.https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/self-help/guides-tools-and-activities/five-steps-to-mental-wellbeing/. Accessed 05.06.22

Rogers, C. (1957). ‘The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change’. Journal of Consulting Psychology, Vol. 21(2), pp.95-103.

Sapin, K. (2013).’ Essential Skills for Youth Work Practice’ (2nd edn), London: Sage.

Power The Fight (2021). ‘The Therapeutic Intervention For Peace (Tip) Pilot Project ‘. Available online: https://yjresourcehub.uk/images/Serious_Youth_Violence/PTF_YJBReport_June2021.pdf. Accessed 05.06.22

UNICEF (2021). ‘Impact of COVID-19 on poor mental health in children and young people ‘tip of the iceberg’ Available online: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/impact-covid-19-poor-mental-health-children-and-young-people-tip-iceberg.Accessed 05.06.22

Wolpert, M., Harris, R., Hodges, S., Fuggle, P., James, R., Wiener, A., Munk, S. (2019). ‘THRIVE Framework for system change’. London: CAMHS Press

Young Minds (2021). ‘The impact of Covid-19 on young people with mental health needs’ . Available online: https://www.youngminds.org.uk/about-us/reports-and-impact/coronavirus-impact-on-young-people-with-mental-health-needs/. Accessed 05.06.22

Biography:

Sally Carr MBE is a nationally recognised leader in professional youth work and community development. For over 30 years, she has worked across the statutory, voluntary and private sectors, founding and leading regional and national youth and community work projects. Sally’s innovative and inspirational work has been recognised with several accolades including the Prime Minister’s Award and an MBE. Her contribution to equality, diversity and inclusion, as well as social justice, has garnered awards at regional and national levels. Since 1988, Sally has dedicated her life to LGBTQ+ equalities work and youth mental health. She continues to contribute to youth and community development in the UK and internationally, including as a Non-Executive Director of various youth organisations. Sally is currently leading a project to develop a model of Therapeutic Youth Work.

Twitter: @SallyCarrMBE

LinkedIn: http://linkedin.com/in/sallycarrmbe