Article: Colonised youth

This paper looks at youth identity, and how responses to young people tend to undermine understanding of this group’s economic and political position.

Introduction

Young people are understood to be intrinsically challenging (a group that is seen both as a threat and the object in need of support); they are ‘this’ because they are ‘that’ – the young are challenging because they are young/immature/childish/adolescent/not grown up – all these epithets might be regarded as insults if applied to ‘non-youth’ (adults). This is an inherently deficit perspective that if applied to other groups (say people of colour, women, LGBT groups) would quite appropriately meet with mass consternation and in many contexts potential legal consequences.

In this paper I will look at youth identity and how, like other groups subjected to discrimination and prejudice, political responses to this group are enmeshed in considerations, which undermine understanding of this group’s economic and political position via age related deficit categorization.

Current circumstances: Youth identity

Youth, being youth, from the adult perspective an ‘other’, can be understood to be an outsider/outcast group. However, youth are also a diverse group in terms of age; in the UK for example it can encompass everyone from 13 to 19, other contexts take this category to be anything from 10 to 40. Of course youth diversity extends over ethnic, social, religious, sexuality and relative ability considerations and this has intersectional consequences.

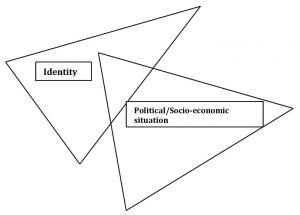

Thus the issues relating to ethnic or life-style identity groups and youth can be understood to have a broadly dual foundation (see Figure 1 below). However these issues are usually addressed independently; one consideration or the other is thought to be crucial or primary.

Figure 1: Dual foundation of issues relating to youth and other identity groups

At the same time youth can be understood as a group subjected to incessant discrimination and inequality (Belton, 2010). Variously they are, among other restrictions, unable in law to independently purchase a huge range of commodities and services, including the buying, selling or renting of property, apply for a passport, vote (so being unrepresented politically), receive benefits in their own right, pay taxes, smoke, drive a car, or gain anything but the most restricted, often illegal and poorly paid work. Youth are legally restricted right across the sexual horizon (even in mid/late teenage they are often as good as regarded as non-sexual beings), they are disallowed from frequenting certain forms or categories of entertainment, buying or consuming alcohol and have rights that are only translatable via adult duties and responsibilities. Added to all this, increasingly across the globe, youth are by law required to attend and be subject to the disciplinary regimes and surveillance of state institutions and their professional gaze for the better part of their time. In this controlled environment they are obliged to ingest an educational curriculum they have little or no say in (Clark, 1975). Although ‘one way education’ is not education at all; it is a form of indoctrination (Belton, 2009). Again, if I were describing almost any other group, the social recrimination in the face of this lack of basic civil rights would amount to deafening condemnation of any authority that acted as steward to these restrictions of freedom of action and choice.

In the light of these circumstances it is not surprising that youth have traditionally rebelled against the values of adult society in terms of cultural and counter-cultural responses, but also outright (if limited) rebellion, uprising and what is labelled ‘mindless violence’, when any response other than aggressive insurgence would seem illogically passive. Like other minority groups, youth justifiably have little or no confidence in social institutions and as a group display scant interest in or enthusiasm for mainstream politics (see Mattson, 2001) amazingly to the dismay of many political groups. Like other minority groups (generally) youth often look to social networks for security, support and interaction (see Belton el al, 2016; Bunescu, 2014; McGarry, 2010; Milcher, 2011; Nicolae, 2013; Pusca, 2012). These resorts are currently under attack from adult society; almost any informal group of young people being quickly labelled ‘a gang’ and therefore a threat. At the same time, designated youth facilities are limited or completely eradicated due to economic belt tightening. The latter are replaced by formalised, not unusually commercialised, local bastions of institutional state control; employability projects, training agencies, targeted youth provision – ‘rogue’ (free) youth are literally ‘hunted’ (see Bright, 2015). Similarly to Roma, youth as a result have little time or confidence in the spectre of the ‘official’ and are much more likely to look to social networks as their port in a storm (Belton, 2015).

Youth discourse

Youth are seen to be deficient because of their relative immaturity; they are understood to lack age. While family or parental position are pertinent in terms of relative wealth, housing and so on, the reaction to youth and their relative position are almost exclusively set in an age corral.

Prejudice and discrimination give rise to a multifaceted set of phenomena, altering over time, place and arguably sometimes from person to person. It is also dependent on the position any particular individual or group find themselves in, relative to the wider community or society. The nature of prejudice is manifested in and through a range of social, cultural and economic factors. Racism (for example) has become a functional means to explain disadvantage – unemployment, low life expectancy, slum housing; it has been made a ‘route one’ rationalization of disadvantage and it is what is, in the main, targeted to alleviate the same (Gatti et al, 2016). At an institutional and state level, this enables the denial of political responsibility by blaming popular prejudices for failures to act politically and socially.

The circumstances of youth are also polygonal; different contexts, including national, regional, familial, religious and cultural mores prevail over the category. Youth populations are also subject to differing responses according to their intersectional profile; faith, sexuality, gender, ethnicity and so on. However, across these considerations they are defined and confined by an ‘age enclosure’.

The perspective of both racial groups and youth essentially reflects the promotion of false consciousness within and towards these groups. The story we are confronted with when thinking of racial difference is an ethnic discourse, addressable via the promotion of an ethical / moral response (‘rights’). Youth too are addressed socially by way of ethical and morality discourse, but this is premised on the duties and responsibilities of adults; youth have little if any authority or influence over how their position is responded to – it is literally out of their hands (despite Articles 12 and 13 of the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child).

The above undermines and detracts from the possibility of understanding these groups as essentially the victims and prey of the capitalist social formation; it conflates and camouflages the social imperative of inequality inherent in state sponsored capitalism (Heathfield and Fusco, 2016). As such, issues pertaining, or said to be pertaining, to minority ethnic groups are made to appear almost purely an uncomplicated struggle for rights by and for an oppressed ethnic minority against the ignorance and prejudice of host communities, while youth issues are predominately interpreted as an inept response by adults to legislation and addressed in the language of professional ethics and family morality. This interpretation prevents recognition of a continuance of the deficit response to young people and the perpetuation of their inequality and control.

At the same time, while identity as race, ethnicity and culture are often relatively ethereal categorisations (Belton, 2005a, 2005b) the resultant disadvantage (in a direct experiential sense) is mechanistic – it is a consequence of the interplay between their economic and social position, which is instrumentally related to the nature of the social formation over and above relative identity (Milcher, 2011). Yes, racism and bigotry are present, but they are at least as much a product of disadvantage as they are the cause of it. Here one can see such social malevolence as a by-product of capitalism and that youth can be said to be in much the same boat: they are a categorical consequence of the social formation; their circumstances are often exacerbated by intersectional considerations; they are ‘this’ but also ‘that’.

However, as many often seem to ‘ethically disappear’ into host communities after achieving a level social economic parity, one is left to conclude that race is a secondary causation in terms of the experience of disadvantage. Youth too vanish as they reach adulthood; they achieve equivalence with age that allows entry into society. This demonstrates that age as such was never the cause of their relative inequality; it was always access to social and economic resources.

The ethnic discourses that have been the basis for apartheid and genocide have been effectively reinterpreted by ‘enlightened’ benefactors, helpers, professionals, activists and academics as the supposed means of addressing what are essentially economic, social and/or political causation. Standing back it is hard not to understand the attempts of these well-meaning groups to ameliorate structures fundamental to the economic formation via an ethnic or racial discourse. It is difficult not to feel that this is a bit like trying to stop a leak in the roof by a change of attitude – the application of subtle psychological tactics and the preaching of moral imperatives to solve hard practical defects. Essentially this saves on tools and replacement materials, but it will not stop the leak; it’ll just get worse. Not quite like buying second hand water canon to address potential rebellion of disaffected youth in the hot days of August but about as pointless.

It is perhaps by now redundant to point out how this chimes with the professional and rights conscious responses to youth that fail to do much more than perpetuate the deficit position of the young by way of moral placebo and calls for adult ethics to be enacted. This is deeply colonial; the social agenda with regard to youth is thus founded on assumed deficiency of age, and so subject to a form of colonial oppression.

The ethnic discourse has influence beyond bland identity. Ethnic minority access to resources and a voice are fundamentally channelled via this narrative, giving rise to what I have elsewhere called (following on from Hall, 1991) ‘Weak Power’ – the means to influence is accessed by defining oneself as the oppressed pariah, which in the process confirms notions of the ‘born victim’, the necessarily oppressed (Belton, 2005a). At once one adopts the psychological disposition that Biko warned that is: ‘The most potent weapon of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed’ (Biko and Stubbs, 1979 p.69). As soon as one accepts one’s oppression one is truly oppressed – which echoes Fanon (1967a, 1967b; Fanon et al, 1965) and what might be understood as the ‘colonial mentality’. Power is maintained by the colonial elite by sustaining a sense of relative powerlessness on the part of the ‘native’ as the ‘wretched of the earth’. The extent to which academic and professional cadres get behind and reinforce this process, the more they help create what Kovats (2003) has called ‘The road to Hell… paved with good intentions’.

Effectively youth are as bound to ‘weak power’ discourses, subject as they are to adult regimes that are close in psychological character to colonial contexts (see Belton, 2010). This being the case we can understand that social and economic mechanisms and circumstances, reinterpreted and understood as almost exclusively arising as cultural, racial or ethnic difference (almost alone), give rise to both internal and external pressures on individuals and groups. For youth, apart from intersectional considerations, relative age is the camouflage. The consequences are the same for continued discrimination, social exclusion, limited opportunities and social tension. In terms of youth, they remain an essentially colonised group.

The propagation of ethnic, racial or cultural difference fits the agenda of the far right wing in terms of segregating ethnic groups effectively without a political or economic reality. They are merely the result of their own category; all they are is what they are and they are restricted by what they are (not their social economic context – which is understood as just another consequence of what they are). This has led to a working through of ‘weak power’ within an identifiable expression of a Weberian social exclusion dynamic; the excluded exclude the included, so making the excluded a sort of faint representation of the included (Parkin, 1979).

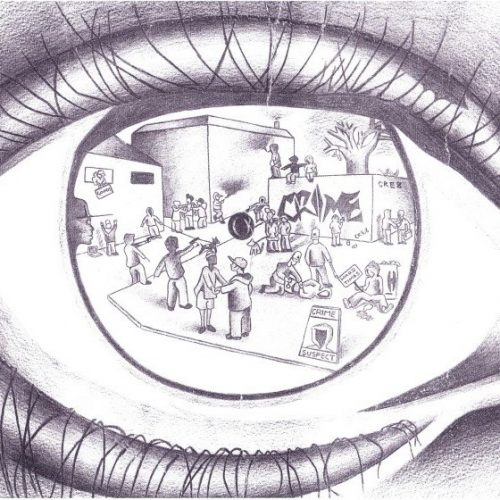

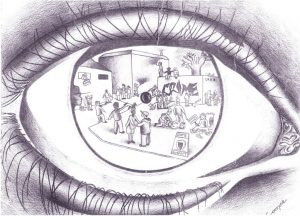

By the same token youth, strapped into a colonial enclosure, are perpetually trapped in a state of constant rebellion that can never evolve into revolution because like ethnic minority groups they do not exist politically or economically in their own right, and socially they are considered only as partly human (they are not considered to be ‘whole’). Effectively not wholly part of society, youth also exclude the excluders by repeatedly rejecting dominant culture and developed their own, using everything from ‘free love’ (Hippies) to actively expressed alienation (Punks), nihilism (Goths) to violence (Mods, Rockers, Skinheads), vandalism (football hooligans) and art (graffiti). Youth has used clothes, music and language as a means of symbolic resistance. Alas that is what this resistance remains: symbolic. Each expression passes away as these cyphers of confrontation are hijacked by commercialism. Thus disarmed as they are reprocessed into ‘style’, fashion and hygienic pastiches of their former state; becoming the garb of retro-rebellious, rising middle-aged sham avant garde.

Image Michael Ilori, by permission.

Youth & Policy is run voluntarily on a non-profit basis. If you would like to support our work, you can donate below.

Last Updated: 26 September 2017

References:

Belton, B. (2005a) Gypsy and Traveller Ethnicity. London: Routledge.

Belton, B. (2005b) Questioning Gypsy identity. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Belton, B. (2009) Developing critical youth work theory. Rotterdam, the Netherlands: Sense

Publishers.

Belton, B. (2010) Radical youth work. Lyme Regis, Dorset: Russell House.

Belton, B. (2015) Questioning ‘Muslim Youth’: Categorisation and Marginalisation, chapter 9 in: Bright, G. (ed.) Youth work: Histories, Policy and Contexts. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Belton, B., Raykova, A., Garcia Lopez, M.A., Paddison, N. (2016) Roma Youth Participation in Action. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Biko, S., Stubbs, A. (1979) I Write What I Like. New York: Harper & Row, 1979.

Bright, G. (ed.) (2015) Youth work: Histories, Policy and Contexts. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bunescu, I. (2014) Roma in Europe: The Politics of Collective Identity Formation. Farnham,

Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Group.

Clark, T. (1975). The oppression of youth. New York: Harper Colophon.

Fanon, F., Sartre, J. and Farrington, C. (1965). The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove

Press.

Fanon, F. (1967a) A Dying Colonialism. New York: Grove Press.

Fanon, F. (1967b) Black Skin, White Masks. New York: Grove Press.

Gatti, R. Karacsony, S. Anan, K. Ferré, C and Nieve, C (2016) Being Fair, Faring Better Promoting Equality of Opportunity for Marginalized Roma, Washington: World Bank

Hall, Stuart (1991) ‘The Local and the Global’, in A.D. King (ed), Culture, Globialization and the World System, London: McMillan, pp.32.

Heathfield, M. & Fusco, D.(2016) Youth and Inequality in Education: Global Actions in Youth Work. New York: Routledge.

Kovats, M. (2003) The Politics of Roma Identity: Between Nationalism and Destitution OpenDemoracy [online] July. Available from:

https://www.opendemocracy.net/people-migrationeurope/article_1399.jsp [Accessed 1 April 2016].

McGarry, A. (2010) Who speaks for Roma? New York: Continuum.

Mattson, K. (2001) Engaging Youth. New York: Century Foundation.

Milcher, S. (2011). On Vulnerability and Labour Market Discrimination of Roma.

Saarbrücken: Südwestdeutscher Verlag für Hochschulschriften.

Nicolae, V. (2013). We are the Roma! London: Seagull Books.

Parkin, F. (1979). Marxism and Class Theory. New York: Columbia University Press.

Pusca, A. (2012). Roma in Europe. New York: International Debate Education Association.

Biography:

Dr Brian Belton is Senior Lecturer at YMCA George Williams College.